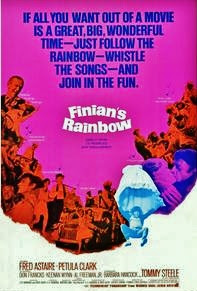

October

9, 1968 Warners 145 minutes

Nowadays a Bway musical can take decades before making it

to the screen, but in 1968 when Finian's

Rainbow was finally filmed, it was overdue by an unheard-of 21 years. Not

that it wasn't in development long before. In the mid-'50s an animated version

was in the works (with Sinatra, Satchmo and Ella Logan as voices), but

thankfully abandoned. One can imagine the sort of Disney-fied adaptation the

times would've called for in softening the pointedly provocative racial

elements. A decade later, Warners pulled it out of their long-shelved file in

response to the gold rush for musicals after The Sound of Music soared. But after two decades Finian was a bit stale in the story

department; which, let's face it, is nothing but a heaping bowl of malarkey--a

lopsided leftist fairy tale with capricious rules of fantasy, fearlessly preachy,

unaplogetically silly. It survives--and it does to this day--only to support a score

that justifies such lunacy, composed by the woefully un-prolific Burton Lane.; with

lyrics by the incomparable E.Y. Harburg, whose wit and invention were best

released when given freedom to delve into the fantastic. Harburg conceived the

show in response to anti-Communist hysteria afoot in the post-war Senate--in

particular a couple of Southern blowhards whose racism made Harburg fume. His idea was to turn a bigot black to

experience his own prejudice, but the idea only clicked when paired with

another story he'd been mulling, that of a leprechaun chasing after a stolen

pot of gold. (Not exactly a natural leap--but no matter.)

The Bway production arrived in January '47, another pearl

on the string of the post-war Golden Age musicals; when such pearls burst forth

with regularity after R&H's Oklahoma Fort Knox Burton Lane

Magnolias are sentimental

Persimmons are que-er

Snapdragons won't pay no rental

This time of the year.

But it's Harburg all right:

We can't be bothered with

a mortgage man

This Time of the year

You don't really notice the number morphing into an unseen

train bringing the story's hero. It's a real star entrance cue, tho it doesn't

play like one; no following number for Woody to explain himself. Instead the

show moves on, introducing Finian and daughter, Sharon--and it is she who sings

the show's biggest hit, and the first of two consecutive "Irish"

tunes. "How Are Things in Glocca Morra?" has never done much for me

(that cheap Irish sentiment, as Finian himself calls it), but "Look to the

Rainbow" has a nice lilt to it, and tho both tunes are reprised thru-out

much of the show, they conclude the Irish portion of the score. "Old Devil

Moon" shifts the mood, a ballad that really drives--and 65 years later still

feels free of cliche. It's a tune Rodgers, Loesser or Styne would have been

proud to have written. Of the leprechaun's two songs--both waltzes--"Something

Sort of Grandish" has the better melody (a sprightly madigral) but

"When I'm Not Hear the Girl I Love" exhalts more on its lyric. "If

This Isn't Love" recalls great Rodgers & Hart standards such as

"Falling in Love with Love," and more obviously, "This Can't Be

Love"--and who better than the Master to emulate? But Harburg & Lane

show their evolving musical vocabulary with the production numbers ending the

first act and beginning the second. "That Great Come-and-Get-It Day"

is a Come-to-Jesus rouser, with an exquisite folk-sounding middle section

("Bells will ring in every steeple..."); an impudently optimistic

affirmation from the man who wrote "Brother Can You Spare a Dime."

But the familiar Harburg comes forth in "When the Idle Poor Become the

Idle Rich," which was enuf to incite Red baiting from the more hysterical

quarters of Communist witch hunters. Equality? Never! It didn't help that this

was the first Bway musical to racially integrate its cast within musical numbers. The first of two "black" numbers,

"Necessity" ("the maximum that a minimum thing could be")

came late in the first act. It was a guaranteed crowd pleaser; as was the

second act's "The Begat," meant for a Negro quartet. Both are usually

solidly put over by their performers, but excuse me if I note these are of far

less musical sophistication than the rest of the score, which--unlike with

Gershwin--has a whiff of condescension about it. I'm just saying. According to

John Lahr (who looks frighteningly like one of the sharecroppers in the chorus),

brilliant as the score is, Lane had a hard time working with Harburg, who would

absurdly claim 97% credit for the show--and resent Lane's acclaim for the

music. They no longer spoke to each other by the show's opening; and sadly

never collaborated again. Neither would have a hit like this again, either.

After being in family hands since its inception, Jack

Warner sold his studio in 1967 for $32 million to 7Arts Productions. (whose co-chairman

was Ray Stark)--and tho he stayed around to oversee, Warner no longer had much

say in staffing decisions. But it was he who matched Finian's Rainbow to Petula Clark, after seeing her perform at the

Cocoanut Grove. She had acted in films in England

as a child, but was known only as a singer in America Radio

City Music

Hall Kentucky

The movie gets off on the wrong foot with the opening credits.

Musically it's fine: Petula crooning "Look to the Rainbow," a capella

at first, then swept up by the studio orchestra. We're watching the backs of

two vagabonds, an old man and his daughter, on their journey across the land. But

would they really be trudging up steep mountain peaks, across glaciers,

teetering over the Grand Canyon , always with

luggage in hand? Their search criss-crosses America Fort Knox California

Is it surprising that Petula Clark has nearly as much

appeal as Julie Andrews in The Sound of

Music? She's lovely, she's fresh, well-sung, slightly rough around the

edges--another Brit embraced by Americans. The story finds her branded a

witch--and there is something a little bewitching about her. Tommy Steele

completes his trio of Hlwd musicals as a leprechaun--his Cheshire cat grin

practically devouring the screen. Coppola thought him all wrong for the part,

but was stuck with Landon's choice. He wanted another Brit, Donal Donnelly, who

had just made a minor splash in the film The

Knack, and How to Get It, and could convey the requisite shyness of the

character. Shyness was something Steele

couldn't get arrested for. Some of his scenes are unendurable--one particularly

puzzling longeur has him "dancing" a one sentence question--over

several attempts. I don't mind him so much in his musical numbers--he is a polished

peformer, and moves unusually well. One role Coppola cast by himself was the

movie's romantic lead, Woody. True to his indie aspirations, he chose a minor

TV actor, vocalist and jazz musician, Don Francks--a Canadian who'd starred as Kelly in the ill-fated '65 musical, (about

a man who jumps off the Brooklyn Bridge) which played but a single performance

on Bway. He has a smooth pop voice ("Not in the Gordon MacRae vein,"

according to Coppola) and sounds especially fine on "Old Devil Moon,"

as does Petula. He has an inviting presence; looks like a cross between Jason

Bateman and Rob Lowe, but is a bit too mellow to radiate star charisma. For the

comically bigoted Senator, they could hardly do better than Keenan Wynn, absent

from musicals since Kiss Me Kate and Annie Get Your Gun.. Interestingly, he

looks every bit as convincing (perhaps even more appealing) as a black man. He

completes a happy quartet joining Avon Long, Roy Glenn and Jester Hairston on

"The Begat," an amusing diversion. The other "black" song

from the show, "Necessity" was filmed but left on the cutting room

floor when the movie ran too long. Better they had trimmed more of the scenes. For

Susan the Silent, Astaire pushed for his final dance partner, Barrie Chase, but

Coppola deemed her too polished and too old, and chose a local dance student,

Barbara Hancock--a dead ringer for comedian Amy Schumer. She gets a moment of

her own, a Rain Dance Ballet--utilizing that Camelot forest again, set to an untypical arrangement of "Old

Devil Moon" (Ray Heindorf's scoring of Lane's melodies is as superlative

as it was in The Music Man--and

earned, along with Sound, the film's only Oscar nominations.) There's far too

much plot and staged business that drags out in the second half, which Coppola

now repeatedly laments. He left Landon to edit the film, moving quickly on to The Rain People--the sort of indie

cinema he preferred. but not the sort of blockbuster features he would shortly

become famous for.

Is it surprising that Petula Clark has nearly as much

appeal as Julie Andrews in The Sound of

Music? She's lovely, she's fresh, well-sung, slightly rough around the

edges--another Brit embraced by Americans. The story finds her branded a

witch--and there is something a little bewitching about her. Tommy Steele

completes his trio of Hlwd musicals as a leprechaun--his Cheshire cat grin

practically devouring the screen. Coppola thought him all wrong for the part,

but was stuck with Landon's choice. He wanted another Brit, Donal Donnelly, who

had just made a minor splash in the film The

Knack, and How to Get It, and could convey the requisite shyness of the

character. Shyness was something Steele

couldn't get arrested for. Some of his scenes are unendurable--one particularly

puzzling longeur has him "dancing" a one sentence question--over

several attempts. I don't mind him so much in his musical numbers--he is a polished

peformer, and moves unusually well. One role Coppola cast by himself was the

movie's romantic lead, Woody. True to his indie aspirations, he chose a minor

TV actor, vocalist and jazz musician, Don Francks--a Canadian who'd starred as Kelly in the ill-fated '65 musical, (about

a man who jumps off the Brooklyn Bridge) which played but a single performance

on Bway. He has a smooth pop voice ("Not in the Gordon MacRae vein,"

according to Coppola) and sounds especially fine on "Old Devil Moon,"

as does Petula. He has an inviting presence; looks like a cross between Jason

Bateman and Rob Lowe, but is a bit too mellow to radiate star charisma. For the

comically bigoted Senator, they could hardly do better than Keenan Wynn, absent

from musicals since Kiss Me Kate and Annie Get Your Gun.. Interestingly, he

looks every bit as convincing (perhaps even more appealing) as a black man. He

completes a happy quartet joining Avon Long, Roy Glenn and Jester Hairston on

"The Begat," an amusing diversion. The other "black" song

from the show, "Necessity" was filmed but left on the cutting room

floor when the movie ran too long. Better they had trimmed more of the scenes. For

Susan the Silent, Astaire pushed for his final dance partner, Barrie Chase, but

Coppola deemed her too polished and too old, and chose a local dance student,

Barbara Hancock--a dead ringer for comedian Amy Schumer. She gets a moment of

her own, a Rain Dance Ballet--utilizing that Camelot forest again, set to an untypical arrangement of "Old

Devil Moon" (Ray Heindorf's scoring of Lane's melodies is as superlative

as it was in The Music Man--and

earned, along with Sound, the film's only Oscar nominations.) There's far too

much plot and staged business that drags out in the second half, which Coppola

now repeatedly laments. He left Landon to edit the film, moving quickly on to The Rain People--the sort of indie

cinema he preferred. but not the sort of blockbuster features he would shortly

become famous for.

The Roadshow premiered October 9th at the former Warner, then

Penthouse Theater in Times Square, to lukewarm reviews and little traction,

caught between the just opened Funny Girl,

and the highly anticipated Star!--with

Julie Andrews as Gertrude Lawrence-- on the horizon. Finian lasted but 18 weeks at reserved seats, compared to 72 for Funny Girl, 47 for Oliver! and 23 for the stunning flop that was Star! It collected $5,500,00

in film rentals--among the top 20 films of 1969, and tho it didn't cost nearly

as much as Star! (which made

considerably less) it was still considered a big disappointment. The

less-than-persuasive modernization of the show did little to abate its fading

reputation. But several decades later it would be recognized again, without

apology, and see some regular resurgence. City Center

Roadshow movie musicals were still coming steadily out of

Hlwd--tho not within my reach in LA's far-western suburb of Canoga Park Cupertino Cupertino Santa Clara

Next Up: Oliver!

Next Up: Oliver!

Report Card:

Finian's Rainbow

Overall Film: B-

Bway Fidelity: B+

Songs from Bway: 10

Songs Cut from Bway: 1

New Songs: None

Standout Number: "The

Begat"

Casting: Mostly spot on

Standout Cast: Petula Clark, Keenan Wynn

Sorethumb Cast: Tommy Steele

Cast from Bway: None

Direction: Confused, mildly experimental

Choreography: Rambling, inconsistent

Ballets: B- Susan's “Rain Dance Ballet"

Scenic Design: Scattershot, mix & match

Costumes: Dull, early Gap

Standout Sets: forest glen from Camelot

Titles: Absurd travelogue, with

credits in an

instantly-passe typeface.

No comments:

Post a Comment