February

20, 1968 Paramount 147 minutes

It's the teeth that strike you first. Tommy Steele's

choppers arrive before the rest of him: a chaser of mischievous blue eyes and a

very British mop of sandy hair. He looks like Ringo's cousin. Or Paul's. In

fact he preceded them by a good five years, generally regarded as UK 's first rock 'n' roll star, who charted in England London West End .

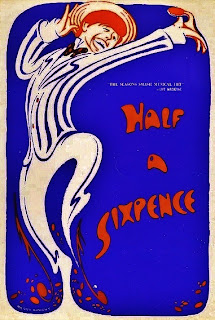

Initially inspired by Noel Coward's Bitter

Sweet, Heneker composed in a more pop idiom, reminiscent of Vincent Youmans

or Jerry Herman. He followed Sixpence

with an even bigger London smash, Charlie Girl, which despite its loosely

"mod" Cinderella motif, wasn't risked on a transfer to America Britain ,

but by its London

You could say that Kipps was born to play Steele, rather

than the other way around. As a tailor-made vehicle it couldn't have been

tighter. The former "English Elvis" tirelessly performs nine

numbers--absent from but two (It's one of the biggest roles in any musical)

including four immense production numbers that constitute the only word-of-mouth

the show really needs. In an era when British musicals were still rarely

exported to

You could say that Kipps was born to play Steele, rather

than the other way around. As a tailor-made vehicle it couldn't have been

tighter. The former "English Elvis" tirelessly performs nine

numbers--absent from but two (It's one of the biggest roles in any musical)

including four immense production numbers that constitute the only word-of-mouth

the show really needs. In an era when British musicals were still rarely

exported to .JPG) Aside from smilin' Tom, the supporting cast is relatively

lackluster. Neither Julia Foster nor Penelope Horner leave much impression as

Kipps' two women, and except for his brief bursts of dancing, Grover Dale--the

one other recruit from Bway--is nearly color-less. His

sole distinction is possession of the longest legs prior to Tommy Tune. On Bway, the hammy actor,

Chitterlow, earned James Grout a Tony nomination. (He's as unknown to me as I'm

sure he is to you), so by that measure upgrading the role on screen would be

Cyril Ritchard (Peter Pan's Captain

Hook--and the campiest one ever) Tho it is one of his more restrained

performances, Cyril does try our patience, enacting campy melodramas for Kipps

within seconds of meeting him. But Ritchard was a stage actor primarily

(another one too big for the screen); and this was his only film appearance

after 1948. It was also the final film for director George Sidney. He was only

51, but had directed features for 25 years, among them: The

Aside from smilin' Tom, the supporting cast is relatively

lackluster. Neither Julia Foster nor Penelope Horner leave much impression as

Kipps' two women, and except for his brief bursts of dancing, Grover Dale--the

one other recruit from Bway--is nearly color-less. His

sole distinction is possession of the longest legs prior to Tommy Tune. On Bway, the hammy actor,

Chitterlow, earned James Grout a Tony nomination. (He's as unknown to me as I'm

sure he is to you), so by that measure upgrading the role on screen would be

Cyril Ritchard (Peter Pan's Captain

Hook--and the campiest one ever) Tho it is one of his more restrained

performances, Cyril does try our patience, enacting campy melodramas for Kipps

within seconds of meeting him. But Ritchard was a stage actor primarily

(another one too big for the screen); and this was his only film appearance

after 1948. It was also the final film for director George Sidney. He was only

51, but had directed features for 25 years, among them: The

The movie begins somewhat promising; not swooping down on

an Austrian Alp, perhaps, but offering pastoral English landscapes to soothe

our wanderlust. And starting with an added backstory, the sealing of a

childhood bond between Arthur Kipps and Ann Pornick; ruptured when the orphaned

Kipps is sent to apprentice with tyrannical draper, Shalford in Folkestone--the

influence of Dickens quite obvious here. A lovely credit sequence (shot by

cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth) chronicles Kipps' journey across England

The second act runs some 15 minutes before another song.

But it's probably the best in the film; a celebration of the wedding photo:

"Flash, Bang, Wallop!" The scene owes a lot to Cukor's "Get Me

to the Church on Time" from MFL.

There's a similar Edwardian pub-crawl feel, and a raucous dance perfectly

framed--but too little too late. Prior to this we slog thru Kipps, with new

fiancee, Helen, taken to Downton Abbey (like Eliza to Ascot )

and predicatably proving an embarrassment. By coincidence, Ann is also in

attendance, as a servant--and coming to her defense, Kipps insults hosts and

guests alike, and runs off to propose to his childhood bride--who even after

this moment of chivalry acts more petulant than grateful. The fault isn't

entirely Julia Foster's, but

her Ann is

really awful; immature, strident,

quite the shrew, without entitlement

to be so.

She's one of the least appealing

musical heroines I can think of. Even her solo is less an expression of feeling

about love or hope, but a rejoinder to the very idea of self-improvement--the

title says it all: "I Know What I Am." You sure can't say the same

for Kipps, not from his perspective or ours. He crudely dismisses the

privileged class (but doesn't curry our sympathy by taunting violence), then

once married to a servant girl he not only courts the upper classes, he berates

Ann for her failure to share his enthusiasm. Whatsmore, his current home,

inherited from his grandfather, seems palatial enuf already--certainly for

someone who's slept most of his life in a cellar. And how unsporting of Kipps

to be building an 11-bedroom mansion while his old best buddies are left to

slave for Shalford. Once he learns the fortune is lost, however, he regains

perspective, and finds his (and supposedly our) values. On Bway. this led to

the final production number, "The Party's on the House (Altho There is No

House"). The song was a Bway replacment for two songs in London

I was scarcely aware of the film's run at Grauman's

Chinese (which was even shorter) as that winter of '68 was eventful for me on

many other accounts. For one, I had just begun high school (L.A's school year

began in January--which makes sense if you think of it--and h.s. started not

with 9th but 10th grade). By then I was firmly in the closet. Not for sexuality

(I was still fantastically naive and unconcerned with that), but for my secret

Bway worship. As an only child whose parents let me pursue what I fancied,

there wasn't much I needed to hide. But among my young peers it was clear I was

riding another cultural bus in the era of acid rock and The Beatles. Our

graduating Junior High class song was "Light My Fire" by the Doors.

Who else but me was listening to Henry,

Sweet, Henry or I Do! I Do!? I

doubt even my newest best friend, Larry Shevick was privy to my private

pursuits, tho he was just as enamored as I of superficial things; glamour,

wealth and success. I went with his family to

I was scarcely aware of the film's run at Grauman's

Chinese (which was even shorter) as that winter of '68 was eventful for me on

many other accounts. For one, I had just begun high school (L.A's school year

began in January--which makes sense if you think of it--and h.s. started not

with 9th but 10th grade). By then I was firmly in the closet. Not for sexuality

(I was still fantastically naive and unconcerned with that), but for my secret

Bway worship. As an only child whose parents let me pursue what I fancied,

there wasn't much I needed to hide. But among my young peers it was clear I was

riding another cultural bus in the era of acid rock and The Beatles. Our

graduating Junior High class song was "Light My Fire" by the Doors.

Who else but me was listening to Henry,

Sweet, Henry or I Do! I Do!? I

doubt even my newest best friend, Larry Shevick was privy to my private

pursuits, tho he was just as enamored as I of superficial things; glamour,

wealth and success. I went with his family to Next Up: Funny Girl

Overall Film: C+

Bway Fidelity: B

Musical Numbers from Bway: 9

Musical Numbers Cut from Bway: 2

New Songs: 2 "This is My World"

"The Race

is On" + 2 from London

Standout Numbers:

"Flash, Bang, Wallop!"

"If the

Rain's Got to Fall"

Worst Ommission: "The Party's on the House"

Casting: Indifferent, unmemorable

Standout Cast:

Tommy Steele

Sorethumb Cast:

Julia Foster

Cast from Bway: Steele, Grover Dale,

Direction: Tired, with feeble "new" touches

Choreography:

Lively, reliant on formations,

conspicuously

proscenium framed

Ballet: None

Scenic Design: Edwardian town & country

Standout Locations: Folkestone

Costumes: J.C. Penney-Lane

Standout Sets: Folkestone pier; wedding pub

Titles: Scenic

English landscapes, over joyful

overture--perhaps the best moments of the film.

Oscar Noms: None

Weird Hall of Fame: "Money to Burn"

a most bizarrely structured number--must see

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

1 comment:

Post a Comment