Like Show Boat,

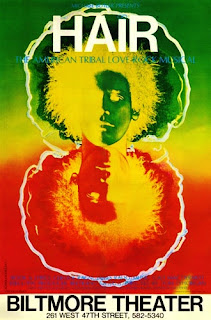

which presaged a revolution in musical theater, Hair which arrived at the tail end of Bway’s Golden Age for

musicals, was precursor to another age. But where it took another 16 years after

Show Boat for Oklahoma

Hair was born in the autumn following the Summer of Love, by two 30-something downtown actors with uptown credits: Gerome Ragni (who was in Richard Burton's Hamlet, and James Rado in Lion in Winter as one of Robert Preston's sons.) But their roots were in The Open Theater and LaMama, which played on the same streets as the nouveau-beatniks filtering into the Village (not to mention SF'sHaight-Ashbury ). Fueled by an rising

anti-war sentiment, Jim & Jerry wrote a good many lyrics before finding

composer Galt MacDermot--who despite his appropriately East Village name, was a

married-with-children, classically-trained, jazz & rock musician, somewhat

older and anything but a hippie. The show came together at the perfect hour to

attract interest from producer Joseph Papp for his initial attraction at the

new Public Theater on Astor Place America Butler

Hair was born in the autumn following the Summer of Love, by two 30-something downtown actors with uptown credits: Gerome Ragni (who was in Richard Burton's Hamlet, and James Rado in Lion in Winter as one of Robert Preston's sons.) But their roots were in The Open Theater and LaMama, which played on the same streets as the nouveau-beatniks filtering into the Village (not to mention SF's

It played for 16 months in San Francisco over '69-'70, but

I wasn't drawn to it, as were my high school peers. It was the great unwashed intruder

on Bway, and I recoiled from its assault on the R&H tradition. But once

Bill played me the album, I had to admit there was something of substance in

the score. I knew it well enuf by the time I saw it on Bway, my first summer in

NY, but by then much of the original cast had left, as had most of the book (if

ever there was one), and the free-for-all performance left far less of an

impression on me than the finely calibrated stagings I saw by Robbins, Prince,

Champion, Bennett and Ron Field. But aside from its historical import, Hair survives because of its score. The

show's progress can be heard thru its recordings. The first, Off-Bway edition,

the one that rocked NYTimes scribe

Clive Barnes off his critical rocker is instructive as a work-in-progress. The

show opened with "Ain't Got No," much more a socio-political

statement than "Aquarius"--which was then buried deep in the second

half. Most of the key songs were already present but the show concluded with a

couple of glaring duds ("Exanaplanetooch" and "The Climax")

that were cut before Bway. No less than 13 songs were added--all welcome, but

none more so than the rousing chant of catharsis from an ever-dimmer tale:

"Let the Sunshine In." Along with better singers and a bigger band

(added horns & sax) the OCR is quintessentially 1968. It certainly felt

genuine enuf for the youth of America

Recordings are countless, and get as arcane as "Hair Goes Latin" by Edmundo Ros. You should hear his "Flesh Failures."

Recordings are countless, and get as arcane as "Hair Goes Latin" by Edmundo Ros. You should hear his "Flesh Failures."

Galt MacDermot has been sadly underused as a theater

composer, but what there is shows proof of an exceptional melodic & rhytmic

intelligence. A fast writer, he said in writing Hair, that if a song didn't come within one morning, it wasn't any

good. His take on Ragni & Rado's hippie cantata was to set it to various

funk & African beats. On top of the free-verse lyrics, Galt found a beat to

match the poetry which at times stole from Allen Ginsberg ("3-5-0-0")

and Shakespeare ("What a Piece of Work is Man"), or simply consisted

of little more than lists; of nasty words, racial epithets, drugs, types of

hair, initials, etc. Many so short they barely got started before they were over.

MacDermot's looseness and tuneful facility brought the songs to life. It's

impossible to think of anyone who could have done it better, or more precisely,

as well. His sophmore effort, which began also with Joseph Papp, was Two Gentlemen of Verona, which is now

unfairly known more for being the "wrong" show to win the Tony over Follies. It is a joyful score, that, even more than Hair,

seems a prisoner

of its aural period--despite being set in the 16th century. Two Gents overflows with music, so much

that the OCR took two discs, something they didn't even grant Sondheim's Follies the first time in a studio. As a

prospective Bway fixture, MacDermot looked to dominate 1972, with two gigantic

musicals opening within weeks of each other. Dude (with Geroge Ragni again) rebuilt the interior of the Broadway

Theater for an enviromental road trip set to a country beat.

seems a prisoner

of its aural period--despite being set in the 16th century. Two Gents overflows with music, so much

that the OCR took two discs, something they didn't even grant Sondheim's Follies the first time in a studio. As a

prospective Bway fixture, MacDermot looked to dominate 1972, with two gigantic

musicals opening within weeks of each other. Dude (with Geroge Ragni again) rebuilt the interior of the Broadway

Theater for an enviromental road trip set to a country beat.

Via Galactica was a Sci-Fi space opera

at the Uris (now the Gershwin --Bway's largest auditorium.) Both sounded

fascinating; both were spectacular flops--which kept Galt away from theater for

a dozen years--lured back by the Public again, this time to set Saroyan to song.

Buttressed with raves, The Human Comedy

was rushed to Bway--where it was nervously and unfairly shuttered after only

two weeks. A shame, for MacDermot's score is amazing. An opera staged like an oratorio, the piece evokes a 1940s

Via Galactica was a Sci-Fi space opera

at the Uris (now the Gershwin --Bway's largest auditorium.) Both sounded

fascinating; both were spectacular flops--which kept Galt away from theater for

a dozen years--lured back by the Public again, this time to set Saroyan to song.

Buttressed with raves, The Human Comedy

was rushed to Bway--where it was nervously and unfairly shuttered after only

two weeks. A shame, for MacDermot's score is amazing. An opera staged like an oratorio, the piece evokes a 1940s

sound while simultaneously feeling modern

(or rather, timeless). It certainly proved MacDermot had range beyond the rock

idiom. Brimming with music--Human Comedy

has over 75 songs--Galt's sound is uniquely his and hard to mistake for anyone

elses. For this reason, it was a good idea to have him adapt Hair for the movie score--a rare occurence

in Hlwd; not even Rodgers would score his own films. The sound feels fresh and

updated without diminishing its late '60s roots. From the first long, long

lead-in to "Aquarius" we are lured into a seductive groove, that

bursts into those iconic, declarative notes, "When the moon..." setting

us at ease that the music is in good hands. For one thing, it's sung better

than before, with top Bway talent featured on many choral passages sung outside

the leads, such as Betty Buckley pouring from the lips of a Vietnamese girl

mouthing "Walking in Space." Unfortunately the film doesn't find narrative

place for a few good songs such as "Frank Mills" and "Abie Baby"

(the

sound while simultaneously feeling modern

(or rather, timeless). It certainly proved MacDermot had range beyond the rock

idiom. Brimming with music--Human Comedy

has over 75 songs--Galt's sound is uniquely his and hard to mistake for anyone

elses. For this reason, it was a good idea to have him adapt Hair for the movie score--a rare occurence

in Hlwd; not even Rodgers would score his own films. The sound feels fresh and

updated without diminishing its late '60s roots. From the first long, long

lead-in to "Aquarius" we are lured into a seductive groove, that

bursts into those iconic, declarative notes, "When the moon..." setting

us at ease that the music is in good hands. For one thing, it's sung better

than before, with top Bway talent featured on many choral passages sung outside

the leads, such as Betty Buckley pouring from the lips of a Vietnamese girl

mouthing "Walking in Space." Unfortunately the film doesn't find narrative

place for a few good songs such as "Frank Mills" and "Abie Baby"

(the Gettysburg

seems a prisoner

of its aural period--despite being set in the 16th century. Two Gents overflows with music, so much

that the OCR took two discs, something they didn't even grant Sondheim's Follies the first time in a studio. As a

prospective Bway fixture, MacDermot looked to dominate 1972, with two gigantic

musicals opening within weeks of each other. Dude (with Geroge Ragni again) rebuilt the interior of the Broadway

Theater for an enviromental road trip set to a country beat.

seems a prisoner

of its aural period--despite being set in the 16th century. Two Gents overflows with music, so much

that the OCR took two discs, something they didn't even grant Sondheim's Follies the first time in a studio. As a

prospective Bway fixture, MacDermot looked to dominate 1972, with two gigantic

musicals opening within weeks of each other. Dude (with Geroge Ragni again) rebuilt the interior of the Broadway

Theater for an enviromental road trip set to a country beat. Via Galactica was a Sci-Fi space opera

at the Uris (now the Gershwin --Bway's largest auditorium.) Both sounded

fascinating; both were spectacular flops--which kept Galt away from theater for

a dozen years--lured back by the Public again, this time to set Saroyan to song.

Buttressed with raves, The Human Comedy

was rushed to Bway--where it was nervously and unfairly shuttered after only

two weeks. A shame, for MacDermot's score is amazing. An opera staged like an oratorio, the piece evokes a 1940s

Via Galactica was a Sci-Fi space opera

at the Uris (now the Gershwin --Bway's largest auditorium.) Both sounded

fascinating; both were spectacular flops--which kept Galt away from theater for

a dozen years--lured back by the Public again, this time to set Saroyan to song.

Buttressed with raves, The Human Comedy

was rushed to Bway--where it was nervously and unfairly shuttered after only

two weeks. A shame, for MacDermot's score is amazing. An opera staged like an oratorio, the piece evokes a 1940s  sound while simultaneously feeling modern

(or rather, timeless). It certainly proved MacDermot had range beyond the rock

idiom. Brimming with music--Human Comedy

has over 75 songs--Galt's sound is uniquely his and hard to mistake for anyone

elses. For this reason, it was a good idea to have him adapt Hair for the movie score--a rare occurence

in Hlwd; not even Rodgers would score his own films. The sound feels fresh and

updated without diminishing its late '60s roots. From the first long, long

lead-in to "Aquarius" we are lured into a seductive groove, that

bursts into those iconic, declarative notes, "When the moon..." setting

us at ease that the music is in good hands. For one thing, it's sung better

than before, with top Bway talent featured on many choral passages sung outside

the leads, such as Betty Buckley pouring from the lips of a Vietnamese girl

mouthing "Walking in Space." Unfortunately the film doesn't find narrative

place for a few good songs such as "Frank Mills" and "Abie Baby"

(the

sound while simultaneously feeling modern

(or rather, timeless). It certainly proved MacDermot had range beyond the rock

idiom. Brimming with music--Human Comedy

has over 75 songs--Galt's sound is uniquely his and hard to mistake for anyone

elses. For this reason, it was a good idea to have him adapt Hair for the movie score--a rare occurence

in Hlwd; not even Rodgers would score his own films. The sound feels fresh and

updated without diminishing its late '60s roots. From the first long, long

lead-in to "Aquarius" we are lured into a seductive groove, that

bursts into those iconic, declarative notes, "When the moon..." setting

us at ease that the music is in good hands. For one thing, it's sung better

than before, with top Bway talent featured on many choral passages sung outside

the leads, such as Betty Buckley pouring from the lips of a Vietnamese girl

mouthing "Walking in Space." Unfortunately the film doesn't find narrative

place for a few good songs such as "Frank Mills" and "Abie Baby"

(the

A Bway revival only five years after closing showed how

far the zeitgeist had moved past Hair,

its flashpoint relevance already so dated by 1977. So what to do for a film at

this late date? Michael Butler was determined to bring it to the screen, and in

partnership with Lester Persky produced the pic for United Artists. Their

surprise choice for director was Czech exile, Milos Forman--coming off his

Oscar win for One Flew Over the Cuckoo's

Nest, who saw in Hair much of his own rebel youth on the streets of Prague

Forman treats the material as romantic American folklore, similar to what Oscar Hammerstein saw inOklahoma

Forman treats the material as romantic American folklore, similar to what Oscar Hammerstein saw in

The casting isn't just smart, it's brilliant. Treat

Williams exudes so much charisma thru his curly locks and impish grin that you

can almost forgive Berger's self-indulgence. He moves & sings well; nowhere

better than in "I Got Life"--a

real show-stopper. As Hud, Dorsey Wright bears strong resemblance in looks and

demeanor to my old NY friend, Al Austin--both men of natural refinement. Don

Dacus (a rock singer moon-lighting as actor) is an amiable, very blonde

Woof--but his role is stripped of any sexual ambiguity (on Bway he crushed on

Berger) and he registers less. Annie Golden plays a sweet, almost imbecilic Jeannie--pregnant

and passively uncertain of the father. She suggests the effects of marijuana on

the teenage brain. With her chipmunk grin and country club sheen, Beverly

D'Angelo makes a shining

The casting isn't just smart, it's brilliant. Treat

Williams exudes so much charisma thru his curly locks and impish grin that you

can almost forgive Berger's self-indulgence. He moves & sings well; nowhere

better than in "I Got Life"--a

real show-stopper. As Hud, Dorsey Wright bears strong resemblance in looks and

demeanor to my old NY friend, Al Austin--both men of natural refinement. Don

Dacus (a rock singer moon-lighting as actor) is an amiable, very blonde

Woof--but his role is stripped of any sexual ambiguity (on Bway he crushed on

Berger) and he registers less. Annie Golden plays a sweet, almost imbecilic Jeannie--pregnant

and passively uncertain of the father. She suggests the effects of marijuana on

the teenage brain. With her chipmunk grin and country club sheen, Beverly

D'Angelo makes a shining foil of Sheila. A band singer who transitioned to

films, her acting career took off from here. The following year she was

fantastic as Patsy Cline to Sissy Spacek's Coal

Miner's Daughter, and in '84 a terrific Stella in a TV Streetcar Named Desire, to Treat Williams' Stanley and Ann-Margret's Blanche. Sadly she's best known now as

foil of Sheila. A band singer who transitioned to

films, her acting career took off from here. The following year she was

fantastic as Patsy Cline to Sissy Spacek's Coal

Miner's Daughter, and in '84 a terrific Stella in a TV Streetcar Named Desire, to Treat Williams' Stanley and Ann-Margret's Blanche. Sadly she's best known now as Even watching the movie now (for the 10th time--and not in two decades) I am shocked at how visceral an impression he still makes. Certain actors in certain roles take on significance beyond the screen and seep into our bloostream. De Niro did it for me in

do

not hook my fixation, it's more the profound honesty of character he exudes. In

the film's opening moments, parting with his father, he conveys such an artful

inarticulateness that speaks volumes. And when he talks, his voice rolls out in

a shy

do

not hook my fixation, it's more the profound honesty of character he exudes. In

the film's opening moments, parting with his father, he conveys such an artful

inarticulateness that speaks volumes. And when he talks, his voice rolls out in

a shy when I'd seen him on Bway during previews for David Mamet's American Buffalo--It didn't help that I hated the play. But it proved his ticket to movie casting agents, and Hair elevated his presence from a vivid supporting role in The Deer Hunter--where he proved equal to the stature of his co-stars: De Niro, Streep, Walken and John Cazale. He graduated to headlining with The Onion Field and Inside Moves (as yet another Vietnam vet) the next year, but oddly, he didn't become the Star he seemed destined for; tho he's worked steadily in supporting roles (Salvador, Do the Right Thing, Godfather III, Terence Malick's Thin Red Line and New World) for nearly 40 years. But nowhere is he more endearing than in Hair.

Michael Weller's screenplay expands beyond what was

secular on stage; where we had only the Tribe without any outsiders. Weller

brings in the rest of us, showing various reactions to the hippie surgence;

fear, repulsion, curiosity, attraction. Not least from Claude--now an Oklahoma Jersey debutante; her brother a

high school dork. The Tribe is reduced to a quartet, just Berger, Hud, Woof and

Jeannie, who is pregnant by one of them. Hud is later revealed as an absent

father; his fiance (who gets the torchy "Easy to Be Hard" but isn't given

a name--the credits list her merely as Hud's fiance) & son another pair of

outsiders who join in the journey. The

show's original anti-war emphasis (carried over from Ragni's days in Viet Rock, an experimental rock musical

at LaMama) was passe by the late '70s, so Weller's script focussed more on the

spiritual and hedonistic qualities of the hippie life; a choice that some--starting

with the authors--considered tantamount to pillage. As one not so attached to

the original show, I find the movie far more involving. Weller's characters and

their interactions connect more deeply with me, conveying a level of intensity that

feels authentic for that time & place. But in the long run the show, above

all, is its music; and Forman & Tharp present the score in stunning

fashion.

It's almost startling that the film starts without music,

at dawn outside a house in Oklahoma New

York Central Park awash in hippiedom, with

Tharp's dancers twitching in stoned abandon; cops on

dancing horses and the

camera twirling around Renn Woods singing the defining opening song. A few

incidents connect Claude to Sheila and the Tribe and a series of short songs lead

into the stoned night--culminating in an explosive "Ain't Got No."

And here we must note how well the music is edited. One of the hardest, and

least well-done elements in movie musicals are the transitions from song to

scene. For once, there's a brilliant intelligence at work on that nuance. The

final cymbal crash of "Ain't Got No" has Claude bolt upright the next

morning; a breathtaking razor sharp cut--that jars us as much as him. For a

welcome change of scene (from Central Park) Weller takes us into Philip Roth

territory next: Sheila's

dancing horses and the

camera twirling around Renn Woods singing the defining opening song. A few

incidents connect Claude to Sheila and the Tribe and a series of short songs lead

into the stoned night--culminating in an explosive "Ain't Got No."

And here we must note how well the music is edited. One of the hardest, and

least well-done elements in movie musicals are the transitions from song to

scene. For once, there's a brilliant intelligence at work on that nuance. The

final cymbal crash of "Ain't Got No" has Claude bolt upright the next

morning; a breathtaking razor sharp cut--that jars us as much as him. For a

welcome change of scene (from Central Park) Weller takes us into Philip Roth

territory next: Sheila's Jersey debutante ball,

which Berger, not only crashes, but arrogantly flaunts his self-styled

liberation, wreaking havoc on a formal banquet table. Of course "I Got

Life" is meant to amaze us--and it

does, tho Berger's underlining "fuck you" is really unearned--it's actually appallingly selfish. Still, it's as joyous as it is improbable--and one of the film's stand-alone highlights. (But why only tits & ass in the list of body parts he's happy to have?--Couldn't the boys in all their no-holds-barred liberation bring themselves to mentioning cock?) A stint in jail affords placement of the song, "Hair," followed by a short playlet with Berger and his parents that sums up the whole national discourse between generations at that time. As his loud-mouthed, soft-hearted mother,

Antonia Ray is priceless--especially in her insistence on washing his

pants. Out of jail the tribe joins a park Be-In, with Claude taking his first

acid trip. "Electric Blues" and "Hare Krishna" are perfect

aural expressions, but the fantasy scenes dreamed up as Claude's hallucinations

are so unlike LSD, they could only come from the minds of psychedelic virgins.

Twyla gets to play with flash mobs for "Where Do I Go," filling and

clearing NY streets while Claude questions his existence. If the movie lacks

the show's anti-war activism, it sure spends a lot of the second half with the army.

It begins at the induction center, where draftees strip for inspection. The

first, a very young Michael Jeter, is exposed with painted red toenails--the

film's allusion to homosexuality as grounds for rejection But then what are we to

make of what follows?: the funky "Black Boys/White Boys" combo, which

Forman takes to camp extremes; cutting between the familiar black & white

female trios, and the male army board, equally drooling --in falsetto-- over the specimens

Antonia Ray is priceless--especially in her insistence on washing his

pants. Out of jail the tribe joins a park Be-In, with Claude taking his first

acid trip. "Electric Blues" and "Hare Krishna" are perfect

aural expressions, but the fantasy scenes dreamed up as Claude's hallucinations

are so unlike LSD, they could only come from the minds of psychedelic virgins.

Twyla gets to play with flash mobs for "Where Do I Go," filling and

clearing NY streets while Claude questions his existence. If the movie lacks

the show's anti-war activism, it sure spends a lot of the second half with the army.

It begins at the induction center, where draftees strip for inspection. The

first, a very young Michael Jeter, is exposed with painted red toenails--the

film's allusion to homosexuality as grounds for rejection But then what are we to

make of what follows?: the funky "Black Boys/White Boys" combo, which

Forman takes to camp extremes; cutting between the familiar black & white

female trios, and the male army board, equally drooling --in falsetto-- over the specimens

before them. It's pretty cheeky and hilarious--but what is it saying?

To gild the lily, here's the nudity provided--two hunks and Claude stripped to

their bare hands for coverage. That and some skinny dipping the night before

constitute the quota for bare asses. Of course Hair was at one time famous most

for its nudity--the collective dropped-trou at the end of the first act, done

under the proviso of standing still (the tableux

vivant was the legal loophole) was a last minute filigree to "Where Do

I Go?" by director Tom O'Horgan. It certainly gave the show another summit

of notoriety. But the uncovered penis has made many appearances on Bway since

'68, and now serves the show more as a cast-bonding experience than a statement

of shock value.

before them. It's pretty cheeky and hilarious--but what is it saying?

To gild the lily, here's the nudity provided--two hunks and Claude stripped to

their bare hands for coverage. That and some skinny dipping the night before

constitute the quota for bare asses. Of course Hair was at one time famous most

for its nudity--the collective dropped-trou at the end of the first act, done

under the proviso of standing still (the tableux

vivant was the legal loophole) was a last minute filigree to "Where Do

I Go?" by director Tom O'Horgan. It certainly gave the show another summit

of notoriety. But the uncovered penis has made many appearances on Bway since

'68, and now serves the show more as a cast-bonding experience than a statement

of shock value.

dancing horses and the

camera twirling around Renn Woods singing the defining opening song. A few

incidents connect Claude to Sheila and the Tribe and a series of short songs lead

into the stoned night--culminating in an explosive "Ain't Got No."

And here we must note how well the music is edited. One of the hardest, and

least well-done elements in movie musicals are the transitions from song to

scene. For once, there's a brilliant intelligence at work on that nuance. The

final cymbal crash of "Ain't Got No" has Claude bolt upright the next

morning; a breathtaking razor sharp cut--that jars us as much as him. For a

welcome change of scene (from Central Park) Weller takes us into Philip Roth

territory next: Sheila's

dancing horses and the

camera twirling around Renn Woods singing the defining opening song. A few

incidents connect Claude to Sheila and the Tribe and a series of short songs lead

into the stoned night--culminating in an explosive "Ain't Got No."

And here we must note how well the music is edited. One of the hardest, and

least well-done elements in movie musicals are the transitions from song to

scene. For once, there's a brilliant intelligence at work on that nuance. The

final cymbal crash of "Ain't Got No" has Claude bolt upright the next

morning; a breathtaking razor sharp cut--that jars us as much as him. For a

welcome change of scene (from Central Park) Weller takes us into Philip Roth

territory next: Sheila's does, tho Berger's underlining "fuck you" is really unearned--it's actually appallingly selfish. Still, it's as joyous as it is improbable--and one of the film's stand-alone highlights. (But why only tits & ass in the list of body parts he's happy to have?--Couldn't the boys in all their no-holds-barred liberation bring themselves to mentioning cock?) A stint in jail affords placement of the song, "Hair," followed by a short playlet with Berger and his parents that sums up the whole national discourse between generations at that time. As his loud-mouthed, soft-hearted mother,

Antonia Ray is priceless--especially in her insistence on washing his

pants. Out of jail the tribe joins a park Be-In, with Claude taking his first

acid trip. "Electric Blues" and "Hare Krishna" are perfect

aural expressions, but the fantasy scenes dreamed up as Claude's hallucinations

are so unlike LSD, they could only come from the minds of psychedelic virgins.

Twyla gets to play with flash mobs for "Where Do I Go," filling and

clearing NY streets while Claude questions his existence. If the movie lacks

the show's anti-war activism, it sure spends a lot of the second half with the army.

It begins at the induction center, where draftees strip for inspection. The

first, a very young Michael Jeter, is exposed with painted red toenails--the

film's allusion to homosexuality as grounds for rejection But then what are we to

make of what follows?: the funky "Black Boys/White Boys" combo, which

Forman takes to camp extremes; cutting between the familiar black & white

female trios, and the male army board, equally drooling --in falsetto-- over the specimens

Antonia Ray is priceless--especially in her insistence on washing his

pants. Out of jail the tribe joins a park Be-In, with Claude taking his first

acid trip. "Electric Blues" and "Hare Krishna" are perfect

aural expressions, but the fantasy scenes dreamed up as Claude's hallucinations

are so unlike LSD, they could only come from the minds of psychedelic virgins.

Twyla gets to play with flash mobs for "Where Do I Go," filling and

clearing NY streets while Claude questions his existence. If the movie lacks

the show's anti-war activism, it sure spends a lot of the second half with the army.

It begins at the induction center, where draftees strip for inspection. The

first, a very young Michael Jeter, is exposed with painted red toenails--the

film's allusion to homosexuality as grounds for rejection But then what are we to

make of what follows?: the funky "Black Boys/White Boys" combo, which

Forman takes to camp extremes; cutting between the familiar black & white

female trios, and the male army board, equally drooling --in falsetto-- over the specimens  before them. It's pretty cheeky and hilarious--but what is it saying?

To gild the lily, here's the nudity provided--two hunks and Claude stripped to

their bare hands for coverage. That and some skinny dipping the night before

constitute the quota for bare asses. Of course Hair was at one time famous most

for its nudity--the collective dropped-trou at the end of the first act, done

under the proviso of standing still (the tableux

vivant was the legal loophole) was a last minute filigree to "Where Do

I Go?" by director Tom O'Horgan. It certainly gave the show another summit

of notoriety. But the uncovered penis has made many appearances on Bway since

'68, and now serves the show more as a cast-bonding experience than a statement

of shock value.

before them. It's pretty cheeky and hilarious--but what is it saying?

To gild the lily, here's the nudity provided--two hunks and Claude stripped to

their bare hands for coverage. That and some skinny dipping the night before

constitute the quota for bare asses. Of course Hair was at one time famous most

for its nudity--the collective dropped-trou at the end of the first act, done

under the proviso of standing still (the tableux

vivant was the legal loophole) was a last minute filigree to "Where Do

I Go?" by director Tom O'Horgan. It certainly gave the show another summit

of notoriety. But the uncovered penis has made many appearances on Bway since

'68, and now serves the show more as a cast-bonding experience than a statement

of shock value.

"Walking in Space" was meant to represent an

acid trip on stage, but on screen becomes a surrealist montage of boot camp.

"3-5-0-0" juxtaposes troop manuevers with anti-war protestors in DC.

"Good Morning Sunshine" has our principals (Berger, Woof, Hud, Hud's

fiancee & child, Jeannie and Sheila) cruising thru the desert in Sheila's

parents' Lincoln

be corny. But from this point forward there are untypically long stretches without music. The process of getting Berger to infiltrate the base and switch places with Claude requires a bit of narrative. But Berger's actions if not stupidly naive, seem just outright clueless. Perhaps Weller's intention is to demonstrate the consequence of such flippance, which has Berger shipped off toViet

Nam

be corny. But from this point forward there are untypically long stretches without music. The process of getting Berger to infiltrate the base and switch places with Claude requires a bit of narrative. But Berger's actions if not stupidly naive, seem just outright clueless. Perhaps Weller's intention is to demonstrate the consequence of such flippance, which has Berger shipped off to

The film opened at the Ziegfeld Theater in NY on March 14,

1979, and tho dismissed by some was largely praised for its creativity, its new

perspective, its pitch-perfect casting and its freshness in direction and choroegraphy.

But the viral popularity of the original show did not catch fire at the box

office--too late to be relevant, too soon for nostalgia. As well as too

sincere, unlike the previous year's Grease--with

its codified period cliches, and monster grosses. Ironically, Hair was an art house hit which didn't

broaden nationwide; earning just $6,800,00 in film rentals--not much better

than The Wiz or Mame. Those were star vehicles, granted, but awful. Hair was, ironically, too special for

mass appeal.

They were the counterculture youth and they scared the bejesus

out of Nixon's America

with those around me. Over time, with the help of

the movie, I'd grown quite fond of Bway's Hair,

and even made a long-weekend jaunt to NY to see the concert put on by Encores

in May 2001. As a musical performance it was alive and vibrant, but fully

staged in Diane Paulus's 2009 revival the show had an (inescapable?) aura of

play-acting about it; feelings, attitudes, venacular both physical & verbal

that felt "researched" rather than felt. But if the cast spiritually

bonded, as Jay Armstrong Johnson tells it, they bonded more in the cult of show-folk

than as shapers of the zeitgeist.

with those around me. Over time, with the help of

the movie, I'd grown quite fond of Bway's Hair,

and even made a long-weekend jaunt to NY to see the concert put on by Encores

in May 2001. As a musical performance it was alive and vibrant, but fully

staged in Diane Paulus's 2009 revival the show had an (inescapable?) aura of

play-acting about it; feelings, attitudes, venacular both physical & verbal

that felt "researched" rather than felt. But if the cast spiritually

bonded, as Jay Armstrong Johnson tells it, they bonded more in the cult of show-folk

than as shapers of the zeitgeist.

with those around me. Over time, with the help of

the movie, I'd grown quite fond of Bway's Hair,

and even made a long-weekend jaunt to NY to see the concert put on by Encores

in May 2001. As a musical performance it was alive and vibrant, but fully

staged in Diane Paulus's 2009 revival the show had an (inescapable?) aura of

play-acting about it; feelings, attitudes, venacular both physical & verbal

that felt "researched" rather than felt. But if the cast spiritually

bonded, as Jay Armstrong Johnson tells it, they bonded more in the cult of show-folk

than as shapers of the zeitgeist.

with those around me. Over time, with the help of

the movie, I'd grown quite fond of Bway's Hair,

and even made a long-weekend jaunt to NY to see the concert put on by Encores

in May 2001. As a musical performance it was alive and vibrant, but fully

staged in Diane Paulus's 2009 revival the show had an (inescapable?) aura of

play-acting about it; feelings, attitudes, venacular both physical & verbal

that felt "researched" rather than felt. But if the cast spiritually

bonded, as Jay Armstrong Johnson tells it, they bonded more in the cult of show-folk

than as shapers of the zeitgeist.

Bway, in the spring of '79 had a burst of activity--tho much of it was the final frail stand of Golden Age giants. Strouse & Adams crashed A Broadway Musical (could there be a more generic title?) a meta-musical about their experience writing a black musical (Golden Boy), as inspired by A Chorus Line. Jerry Herman saw an undeserved quick flop with The Grand Tour. Alan Jay Lerner coerced

play

R&H had first produced back in the '40s, I Remember Mama was a sentimental family saga of Norwegians in San

Francisco, and an obvious candidate for R&H musicalization--which surely

helped lyricist Martin Charnin (emboldened by his success with Annie) to coerce Rodgers into

collaboration. The show, starring a tuneless Liv Ullmann, lasted three months

thru summer. And so Richard Rodgers was done. But not out, as a sparkling fresh revival of

play

R&H had first produced back in the '40s, I Remember Mama was a sentimental family saga of Norwegians in San

Francisco, and an obvious candidate for R&H musicalization--which surely

helped lyricist Martin Charnin (emboldened by his success with Annie) to coerce Rodgers into

collaboration. The show, starring a tuneless Liv Ullmann, lasted three months

thru summer. And so Richard Rodgers was done. But not out, as a sparkling fresh revival of  bringing some comfort to his final days. He

died on December 30th--bowing out hours ahead of the '80s. The year's hits were

by the '70's golden boys: Marvin Hamlisch & Neil Simon's They're Playing Our Song, Sondheim's Sweeney Todd, and Rice & Lloyd

Webber's Evita. More on them in due

time.

bringing some comfort to his final days. He

died on December 30th--bowing out hours ahead of the '80s. The year's hits were

by the '70's golden boys: Marvin Hamlisch & Neil Simon's They're Playing Our Song, Sondheim's Sweeney Todd, and Rice & Lloyd

Webber's Evita. More on them in due

time.

Once I'd attended shows on Bway, road tours felt inevitably

second-rate; even as they rolled out direct from NY. Evita was on its way to

Bway--but felt still unformed. Also in tryout I saw The Grand Tour, and that Oklahoma Island nuclear

accident--the kind of publicity no amount of money could buy. I saw all three again

before I saw Hair on March 31st. With

low expectations going in, the sucker punch it gave me had me returning five

more times within a few weeks; even meriting the acid test. I hadn't been this

obsessed with a movie since New York , New York

I'd moved from Chinatown

to Nob Hill at the end of January--into a two room jewelbox apartment on the

top (4th) floor of a building at the corner of California & Leavenworth. My

bay window, where I set my desk to write, gave me views both west and south.

One block up was Grace Cathedral and the nob of Nob Hill. Several blocks down

was Polk St Manhattan Manhattan Cherry Lane Manhattan

Keaton, Chaplin,

Lloyd & Langdon:, The Silent Clowns.

For three weeks, nearly every night (or day) I trekked to the tiny Surf

theater, off the wind-blown, desolate west coast of SF; shivering in the fog

waiting for the last streetcar back into town. It was a long ride home to Nob

Hill, but my newfound love for Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton (but not Chaplin)

overrode the inconvenience--in those ancient days before video put cinema into

our own hands.

Keaton, Chaplin,

Lloyd & Langdon:, The Silent Clowns.

For three weeks, nearly every night (or day) I trekked to the tiny Surf

theater, off the wind-blown, desolate west coast of SF; shivering in the fog

waiting for the last streetcar back into town. It was a long ride home to Nob

Hill, but my newfound love for Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton (but not Chaplin)

overrode the inconvenience--in those ancient days before video put cinema into

our own hands.

Keaton, Chaplin,

Lloyd & Langdon:, The Silent Clowns.

For three weeks, nearly every night (or day) I trekked to the tiny Surf

theater, off the wind-blown, desolate west coast of SF; shivering in the fog

waiting for the last streetcar back into town. It was a long ride home to Nob

Hill, but my newfound love for Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton (but not Chaplin)

overrode the inconvenience--in those ancient days before video put cinema into

our own hands.

Keaton, Chaplin,

Lloyd & Langdon:, The Silent Clowns.

For three weeks, nearly every night (or day) I trekked to the tiny Surf

theater, off the wind-blown, desolate west coast of SF; shivering in the fog

waiting for the last streetcar back into town. It was a long ride home to Nob

Hill, but my newfound love for Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton (but not Chaplin)

overrode the inconvenience--in those ancient days before video put cinema into

our own hands.

At the start of the '70s I was a high school nerd and show

music addict. By decade's end I was already in retreat from NY and listening to

almost everything but Bway. I caught

up with the pop/rock I'd ignored thru my youth, but it was the so-called New

Wave that finally felt like my pop

music prime. Springsteen, Blondie, Talking Heads, The Specials, The English

Beat, Madness, The Cars, and Elvis Costello (whose lyrics served as dialogue in

a bromance I had that fall with a Berkeley hippie who worked only briefly at

the book-store; sweet James O'Keefe). I first heard the long, driving intro to

"Planet Claire" by the B'52s while riding a bus--and saw the whole of

the '80s flash before my eyes. Never mind there were parallel worlds of disco

& punk and whatnot, this was the flashpoint where I intersected with the

zeitgest. All this was reflected in the screenplay I was writing that year about

twenty-somethings groping thru relationships in San Francisco

on the cusp of the '80s--when Manhattan Manhattan

Next Up: '70s Also Rans

Next Up: '70s Also Rans

Report Card: Hair

Overall Film: A

Bway Fidelity: C-

Songs from Bway: 21

Songs Cut from Bway:

10

Worst Omission:

"Frank Mills"

New Songs: 1 "Somebody to Love"

(used in b.g. only)

Standout

Numbers: "I Got Life"

"Walking in

Space" "Black

Boys/White Boys"

Casting: Exceptional

Standout Cast: John

Savage, Antonia Ray

Cast from Bway: Melba Moore & Ronnie

Dyson (cameos only)

Direction: Sharp, thoughtful, imaginative

Choreography: Tie-dye

Twyla Tharp

Scenic Design: All locations

Costumes: Vintage

East Village

Titles: Crisp font

over opening scenes

Oscar noms: None

Camp Hall of Fame: "Black Boys/White Boys"

Camp Hall of Fame: "Black Boys/White Boys"

No comments:

Post a Comment