For better or worse, I saw more Bway musicals in the '70s

than any other decade. Naturally, because I lived there, for one, but also

because Bway was my first love, the emerald city from childhood that I had to

experiencce if not conquer. And that was my time. So, for this decade's unmade

Bway movie musicals, I have more reference than just acquaintance with the OCR,

and Random House librettos. These I actually saw.

Alan Lerner had made some of the sweetest deals a Bway

player ever got in Hlwd. But as his last few had done much to kill the screen

musical, his luck had run out around the time of

Alan Lerner had made some of the sweetest deals a Bway

player ever got in Hlwd. But as his last few had done much to kill the screen

musical, his luck had run out around the time of  Hepburn wasn't really a box office movie

star, and if Babs couldn't make On a

Clear Day a hit, what reason was there to think Kate could sell a cut-rate

Chanel of a musical; and with her croak of a voice. As with most of Lerner's

scripts the book was labored; more pretentious than witty, more obligatory than

romantic. Andre Previn's music was ersatz Fred Loewe, and tho there are several

nice tunes, there was only one real knockout, the symphonic "Always,

Mademoiselle," which Hepburn vocally destroyed but whose lengthy fashion

parade instrumental is hauntingly beautiful. It's also easily seen in its

entirety on Youtube--from the 1970 Tony Awards. Sadly, Lerner flailed thru

ill-conceived projects for the rest of his life; Lolita, My Love,

Hepburn wasn't really a box office movie

star, and if Babs couldn't make On a

Clear Day a hit, what reason was there to think Kate could sell a cut-rate

Chanel of a musical; and with her croak of a voice. As with most of Lerner's

scripts the book was labored; more pretentious than witty, more obligatory than

romantic. Andre Previn's music was ersatz Fred Loewe, and tho there are several

nice tunes, there was only one real knockout, the symphonic "Always,

Mademoiselle," which Hepburn vocally destroyed but whose lengthy fashion

parade instrumental is hauntingly beautiful. It's also easily seen in its

entirety on Youtube--from the 1970 Tony Awards. Sadly, Lerner flailed thru

ill-conceived projects for the rest of his life; Lolita, My Love,  The problem with turning classic movies into musicals is

the greater the movie, the less likely a musical could equal it. Applause

was a big hit in 1970, the

Palace Theater aglow with its first smash since Sweet Chairty--it swept the Tonys (easily, tho it didn't have to

compete with Company, which was

pushed into the following year by the arbitrary Tony calendar.) It was helmed

by blue-chip talent: Comden & Green, Charles Strouse & Lee Adams, Ron

Field. And it had a genuine (if un-musical) star in Lauren Bacall--who despite

her celluoid fame was at heart, and latter-day practice, a true stage trouper.

Ergo the tuner was less All About Eve

than Margo Channing Tonite! Denied

rights to Joseph Mankiewicz's screenplay at first, the musical was built on

Mary Orr's original short story. Prominently missing from C&G's libretto

was the acid-tongued Addison DeWitt, whose role was cleverly folded into the

producer (a more viable personage to advance Eve's career than a critic), tho

the telescoping reduced Eve to a secondary. if catalytic, character. But

C&G made a fatal flaw in softening Eve's killer instinct. The film has her

angling aggressively to be Margot's understudy--the musical has everyone else

suggesting it, Eve demurely giving in. Takes the sting right out of it, doesn't

it? And why? Thelma Ritter's Birdie was changed into gay hairdresser, Duane Fox

(as if), who hangs out with chorus gypsies (cue production numbers). Applause was the first smash hit I saw

on Bway during its high flush, and it was quite the visceral thrill. I was glad

that Betty & Adolph and Charles & Lee were all back on top; but in the

long run, alas, it was not up to Strouse's gold standard.

The problem with turning classic movies into musicals is

the greater the movie, the less likely a musical could equal it. Applause

was a big hit in 1970, the

Palace Theater aglow with its first smash since Sweet Chairty--it swept the Tonys (easily, tho it didn't have to

compete with Company, which was

pushed into the following year by the arbitrary Tony calendar.) It was helmed

by blue-chip talent: Comden & Green, Charles Strouse & Lee Adams, Ron

Field. And it had a genuine (if un-musical) star in Lauren Bacall--who despite

her celluoid fame was at heart, and latter-day practice, a true stage trouper.

Ergo the tuner was less All About Eve

than Margo Channing Tonite! Denied

rights to Joseph Mankiewicz's screenplay at first, the musical was built on

Mary Orr's original short story. Prominently missing from C&G's libretto

was the acid-tongued Addison DeWitt, whose role was cleverly folded into the

producer (a more viable personage to advance Eve's career than a critic), tho

the telescoping reduced Eve to a secondary. if catalytic, character. But

C&G made a fatal flaw in softening Eve's killer instinct. The film has her

angling aggressively to be Margot's understudy--the musical has everyone else

suggesting it, Eve demurely giving in. Takes the sting right out of it, doesn't

it? And why? Thelma Ritter's Birdie was changed into gay hairdresser, Duane Fox

(as if), who hangs out with chorus gypsies (cue production numbers). Applause was the first smash hit I saw

on Bway during its high flush, and it was quite the visceral thrill. I was glad

that Betty & Adolph and Charles & Lee were all back on top; but in the

long run, alas, it was not up to Strouse's gold standard. Comden & Green's book is by necessity a reduction of

Mankiewicz's leisurely but crackling narrative, tho they manage to get some

good original lines in on their own. Eve caught flirting with Bill explains

they were just playing a game; to which Margot retorts, "One of the

oldest!" Or later, drunk, "praising" Eve: "Isn't she a treasure?.

. . I think I'll bury her." Ethan Mordden brings up a good point that some

of their ideas are improvements. For one thing starting the show with Eve

winning a Tony Award, suggests higher stakes than some old "Sarah

Siddons" trophy won in a musty banquet room (tho in 1950 the Tony Awards

weren't a much bigger affair.) The movie's sexless producer, the Mitteleuropean

Gregory Ratoff, is made over into Robert Mandan's suave silver fox--a real

candidate for Eve's attention and obligation. But the songs don't really make

up for the abbreviated scenario--and often are mere detours. None more so than

the title song, Strouse's most felicitous tune (imagine the words, "

Comden & Green's book is by necessity a reduction of

Mankiewicz's leisurely but crackling narrative, tho they manage to get some

good original lines in on their own. Eve caught flirting with Bill explains

they were just playing a game; to which Margot retorts, "One of the

oldest!" Or later, drunk, "praising" Eve: "Isn't she a treasure?.

. . I think I'll bury her." Ethan Mordden brings up a good point that some

of their ideas are improvements. For one thing starting the show with Eve

winning a Tony Award, suggests higher stakes than some old "Sarah

Siddons" trophy won in a musty banquet room (tho in 1950 the Tony Awards

weren't a much bigger affair.) The movie's sexless producer, the Mitteleuropean

Gregory Ratoff, is made over into Robert Mandan's suave silver fox--a real

candidate for Eve's attention and obligation. But the songs don't really make

up for the abbreviated scenario--and often are mere detours. None more so than

the title song, Strouse's most felicitous tune (imagine the words, "

The musical arrived too late to be serious bait for

Hlwd--another "Big Lady" show and who could they cast as a screen

draw? Not, ironically, the once actual screen star, Bacall now made over into a

stage star, her happiest vocation. Applause

was her triumph and if Hlwd wasn't interested, CBS was persuaded and broadcast

an abridged stage version on TV-studio sets on March 15, 1973--which counts for

something, but not a movie. Coming upon it now (courtesy again of Youtube) is a

reminder of how distinct (and now historical) TV shows looked in early '70s

video, in their primetime drama/soap style. The direction is misguided: Bacall

and Bway veterans, Penny Fuller & Robert Mandan are still playing to the

balcony, which truly squashes whatever subtlety or nuance might be desired.

Lines are ruined in shouted or rushed moments. But the songs, especially the ensembles

look pretty good. The show is abbreviated, with son-of-Mary-Martin, Larry

Hagman (as b.f. Bill) losing his ballad. Harvey Evans plays the very blonde

Duane, minus the required bitchy snap; but worse is Debbie Bowen, who gets to

lead the show's title production number. A cross between Sandy Duncan &

Georgia Engel, she has none of the spunk required to sell it. If not the

original Bonnie Franklin (and why not? She couldn't have been busy, not having

made a TV appearance since an episode of The

Munsters in 1966) couldn't they find one of a thousand other talented Bway gypsies? Mercifully,

"She's No Longer..." was cut and Debbie wasn't back for more. But,

aside from the preservation of the musical on tape--for which we archivists are

always grateful--the production does Lauren Bacall no favors. What was

incandescent about her on stage, is forced and artificial on video. Encores!

unearthed the show in 2008, with Christine Ebersole as Margot and Erin Davie as

Eve., but generated little sense of discovery, making the show's future look

dimmer.

Written by actor Ossie Davis as a vehicle for himself and

wife, Ruby Dee, Purlie Victorious was

a satire of black & white stereotypes in the Jim Crow South, which in 1961

was a broadly played fantasy of Negro retribution. (It was filmed with most of

the Bway cast intact as Gone Are the Days,

in 1963.) But times had changed and the 1970 musical was less a pipe dream than

retrograde coon show--a blackface fable, played by real black faces. Purlie

was a hit--a very soft hit--but enuf to start a new era for black musicals on

Bway. Meanwhile, black cinema was sprouting with more ambitious affirmations: Superfly, Shaft, Coffy, Foxy Brown,

Cleopatra Jones, Cotton Comes to

Harlem--the latter directed by the same Ossie Davis, and released weeks

after the arrival of Purlie. These

were new black archetypes.

Written by actor Ossie Davis as a vehicle for himself and

wife, Ruby Dee, Purlie Victorious was

a satire of black & white stereotypes in the Jim Crow South, which in 1961

was a broadly played fantasy of Negro retribution. (It was filmed with most of

the Bway cast intact as Gone Are the Days,

in 1963.) But times had changed and the 1970 musical was less a pipe dream than

retrograde coon show--a blackface fable, played by real black faces. Purlie

was a hit--a very soft hit--but enuf to start a new era for black musicals on

Bway. Meanwhile, black cinema was sprouting with more ambitious affirmations: Superfly, Shaft, Coffy, Foxy Brown,

Cleopatra Jones, Cotton Comes to

Harlem--the latter directed by the same Ossie Davis, and released weeks

after the arrival of Purlie. These

were new black archetypes.

A live performance of Purlie,

was filmed in a Bronx college auditorium for

CBS broadcast in 1981 (available now, as is almost anything, on YouTube).

Robert Guillaume who replaced Cleavon Little in the last month of the Bway run

and toured, played Purlie, but Melba and Sherman returned to reprise their

roles--with Hemsley now the best known of all, tho still in a supporting part.

The 142 minute running time (with commercials bloated to 3 hours) begs for an

editor's cut. Not having seen the show since July '70, of which I have little

memory, I see now why I never connected with it. Frankly, it's simulatenously

tedious and embarrassing. So creaky a play, it feels like something from the

1920s; with musical numbers sort of jabbed in, and then played out front like

Jolson specials; most shocking is Melba Moore's cartoon deonstruction of

Lutiebelle--so far over the top (where Ruby Dee was human) that she sounds like

Steve Erkel imitating Carol Channing--something you'd never know from the OCR;

her singing voice completely different. But even so, the performances all seem

tired and walked-thru rather than captured for the ages. There's nothing

ageless about Purlie--tho Encores!

did acknowledge it in 2005. But 45 years on, it's hard not to note how close Purlie is to puerile.

Philip Rose assembled another hit with Gary Geld &

Peter Udell five years later, this one based on a Civil War drama starring a mature Jimmy Stewart, Shenandoah. The musical provided John Cullum with a

Tony-winning role, and the show took on an R&H vibe, tho it was less

artfully split between a war drama with many casualties, sweetened with a

series of country-vaudeville numbers, such as "Next to Lovin' I Like

Fightin'" a toe-tapper in the vein of Molly

Brown's "Belly Up to the Bar,

Boys," and "Freedom," an independence cakewalk. Cullum's songs

are all soliloquies--reaching for those Billy Bigelow grace notes. Bway

audiences were starved for something this old-fashioned in 1975, and the show

lasted over 1,000 performances. But having come from the screen, there was

little rush from Hlwd to remake it as a tuner--especially in the

musically-exhausted '70s.

Philip Rose assembled another hit with Gary Geld &

Peter Udell five years later, this one based on a Civil War drama starring a mature Jimmy Stewart, Shenandoah. The musical provided John Cullum with a

Tony-winning role, and the show took on an R&H vibe, tho it was less

artfully split between a war drama with many casualties, sweetened with a

series of country-vaudeville numbers, such as "Next to Lovin' I Like

Fightin'" a toe-tapper in the vein of Molly

Brown's "Belly Up to the Bar,

Boys," and "Freedom," an independence cakewalk. Cullum's songs

are all soliloquies--reaching for those Billy Bigelow grace notes. Bway

audiences were starved for something this old-fashioned in 1975, and the show

lasted over 1,000 performances. But having come from the screen, there was

little rush from Hlwd to remake it as a tuner--especially in the

musically-exhausted '70s.  The Rothschilds is the musical that tore asunder Bock & Harnick, and

for that we are eternally bitter. As the purest purveyors of the R&H

musical line, it seems criminal that their only filmed musical was Fiddler on the Roof. Not Fiorello!,

not She Loves Me, and not The Rothschilds -- which probably has the

most cinematic potential. Doesn't the very title promise grandeur? Yet Bock

& Harnick were criticized for writing another Jewish family story--as if it

were a retread of Fiddler. But if

Tevye represents universal themes of oppression, tradition and expulsion, Mayer

Rothschild's similar beginnings elicit less sympathy knowing they end as

financial barons. Everyone loves a success story, but Jews & Money can be a

polarizing, even inflammatory, subject. Some might think Harnick fans the

flames by having the Roth fils

proclaiming, "It's a curious, dangerous, malady we are all afflicted with/

We want everything/ Everything." The song, which is pleasantly rousing, is

set upon a Semitic musical line where most of the score has the feel of Mozart,

Handel and Haydn--especially in Don Walker's lush orchestrations.

The Rothschilds is the musical that tore asunder Bock & Harnick, and

for that we are eternally bitter. As the purest purveyors of the R&H

musical line, it seems criminal that their only filmed musical was Fiddler on the Roof. Not Fiorello!,

not She Loves Me, and not The Rothschilds -- which probably has the

most cinematic potential. Doesn't the very title promise grandeur? Yet Bock

& Harnick were criticized for writing another Jewish family story--as if it

were a retread of Fiddler. But if

Tevye represents universal themes of oppression, tradition and expulsion, Mayer

Rothschild's similar beginnings elicit less sympathy knowing they end as

financial barons. Everyone loves a success story, but Jews & Money can be a

polarizing, even inflammatory, subject. Some might think Harnick fans the

flames by having the Roth fils

proclaiming, "It's a curious, dangerous, malady we are all afflicted with/

We want everything/ Everything." The song, which is pleasantly rousing, is

set upon a Semitic musical line where most of the score has the feel of Mozart,

Handel and Haydn--especially in Don Walker's lush orchestrations. Still,

comparisons to Fiddler were

inevitably cited; an Oxthodox patriarch with five children (sons instead of

daughters); life in the ghetto (German instead of Russian), devotion to the

Hebrew faith. But where Tevye accepts his lot, Mayer struggles to change his.

Sherman Yellen's skillful libretto took many factual liberties from Frederic

Morton's best-selling biography, and only the earliest chapters, but he shapes

a story compelling enuf to inspire B&H to much of their usual high

standard. The show's downfall is that the second act veers off drastically from

the first; and the first--on its own--is very nearly perfect. Its gilded halls

opening dissolves to the Jewish ghetto, where Mayer and his wife, Gutele dwell

in "One Room"--a song that is enchantment itself, and a glorious

example of Jerry Bock's melodic felicity. "He Tossed a Coin"--a

showpiece for Mayer--is a street market sales pitch. In "Sons" we see

the passage of time as his progeny are born and come of age. One of director

Michael Kidd's better ideas has the five boys flee a pogrom into the cellar,

and come out moments later, grown men. (A tip of the hat, to Dainty June's

Newsboys growing up under a strobe light shuffle.) "Everything" is a

haunting minor-key hora that's always been among my favorite songs in the

score, and "Rothschild & Sons" is joy incarnate. There are

musical delights in the second act, but they're more academic than narratively

engaging. Were the show to conclude on the Sons heading out to conquer the

capitals of

Still,

comparisons to Fiddler were

inevitably cited; an Oxthodox patriarch with five children (sons instead of

daughters); life in the ghetto (German instead of Russian), devotion to the

Hebrew faith. But where Tevye accepts his lot, Mayer struggles to change his.

Sherman Yellen's skillful libretto took many factual liberties from Frederic

Morton's best-selling biography, and only the earliest chapters, but he shapes

a story compelling enuf to inspire B&H to much of their usual high

standard. The show's downfall is that the second act veers off drastically from

the first; and the first--on its own--is very nearly perfect. Its gilded halls

opening dissolves to the Jewish ghetto, where Mayer and his wife, Gutele dwell

in "One Room"--a song that is enchantment itself, and a glorious

example of Jerry Bock's melodic felicity. "He Tossed a Coin"--a

showpiece for Mayer--is a street market sales pitch. In "Sons" we see

the passage of time as his progeny are born and come of age. One of director

Michael Kidd's better ideas has the five boys flee a pogrom into the cellar,

and come out moments later, grown men. (A tip of the hat, to Dainty June's

Newsboys growing up under a strobe light shuffle.) "Everything" is a

haunting minor-key hora that's always been among my favorite songs in the

score, and "Rothschild & Sons" is joy incarnate. There are

musical delights in the second act, but they're more academic than narratively

engaging. Were the show to conclude on the Sons heading out to conquer the

capitals of  Two Gentlemen of Verona is a one-of-a-kind musical that

blew in as a breeze from

Two Gentlemen of Verona is a one-of-a-kind musical that

blew in as a breeze from

None of this invalidates the screen potential of the

musical--which could, in the right hands, have been as unique and delightful as

the stage version. Guare's thrust with the story is about the attraction &

draw of youth to the Big City ; Verona to Milan in the play, but it could be Puerto Rico to New York , or Trinidad to London , Mexico

What a shame Bob Fosse didn't make a film out of Pippin.

It was more deserving of his talents (not to mention his fans) than the

egregious model-murder story, Star 80 that

capped his film career. The Bway musical's success was unduly credited to his

creative genius, and enuf of a smash hit to attract film interest., and in

Stephen Schwartz's lite-rock score had some undeniable youth appeal. (A teenage

Michael Jackson made a record of "Corner of the Sky") It was an

Everyman tale, and could've been cast with every, or any man: William Katt,

maybe or Treat Williams, if not later, Travolta. Ben Vereen is the opposite of

"everyone," but a polished entertainer (and Tony winner for this

role) who would be hard to better. Fastrada, Pippin's sexy step-mother is a

natural for Ann-Margret; and the widow, Catherine. could find original Jill

Clayburgh back in the role, having crossed over into films. But beyond that,

Fosse's cinematic style, honed thru the '70s could have found endless

possibilities in the palette. But then again, he had struggled with the

emptiness of the show on stage, so it's not hard to see why he'd be reluctant

to revisit it.

What a shame Bob Fosse didn't make a film out of Pippin.

It was more deserving of his talents (not to mention his fans) than the

egregious model-murder story, Star 80 that

capped his film career. The Bway musical's success was unduly credited to his

creative genius, and enuf of a smash hit to attract film interest., and in

Stephen Schwartz's lite-rock score had some undeniable youth appeal. (A teenage

Michael Jackson made a record of "Corner of the Sky") It was an

Everyman tale, and could've been cast with every, or any man: William Katt,

maybe or Treat Williams, if not later, Travolta. Ben Vereen is the opposite of

"everyone," but a polished entertainer (and Tony winner for this

role) who would be hard to better. Fastrada, Pippin's sexy step-mother is a

natural for Ann-Margret; and the widow, Catherine. could find original Jill

Clayburgh back in the role, having crossed over into films. But beyond that,

Fosse's cinematic style, honed thru the '70s could have found endless

possibilities in the palette. But then again, he had struggled with the

emptiness of the show on stage, so it's not hard to see why he'd be reluctant

to revisit it. With movie interest absent, the stage show was filmed for

video preservation--an ever increasing alternative now that the movie musical

was growing extinct. Videotaped in Hamilton, Onatrio--of all places--in 1981,

the production brought Ben Vereen, Christopher Chadman (as Pip's half-bro) and

sexy John Mineo (as one of the players) back to their original roles. William

Katt was Pippin, and Chita Rivera, a Star Fastrada--a rare chance to see her

stage magnetism in context. And for Granny, er--Berthe (the swan song of Irene

Ryan on Bway) was none other than Martha Raye (composer Hugh Martin's favorite

singer) to conduct the sing-along, "No Time at All." But the show's

virtues are hard pressed to cover its flaws. The book is short on depth or

emotion, and the comedy is mostly in anachronism, or breaking character to

comment on the production. And tho I confess to playing the OCR (produced by

Phil Ramone) for countless hours as a teenager (while I learned to juggle),

it's not a score that ages well like wine. I hadn't seen the show in years,

when I caught an acclaimed Deaf-West production at the Taper in LA. but without

Fosse's gimmicks, the play's bones were so bare I could hardly wait till it was

over. Diane Paulus, Bway's latest "wunderkind" director took on Pippin in 2013, after her previous--and

sometimes controversial--resuscitations of Hair

and Porgy & Bess. Her solution to

the play's hollow center was to drape it in Cirque de Soleil

With movie interest absent, the stage show was filmed for

video preservation--an ever increasing alternative now that the movie musical

was growing extinct. Videotaped in Hamilton, Onatrio--of all places--in 1981,

the production brought Ben Vereen, Christopher Chadman (as Pip's half-bro) and

sexy John Mineo (as one of the players) back to their original roles. William

Katt was Pippin, and Chita Rivera, a Star Fastrada--a rare chance to see her

stage magnetism in context. And for Granny, er--Berthe (the swan song of Irene

Ryan on Bway) was none other than Martha Raye (composer Hugh Martin's favorite

singer) to conduct the sing-along, "No Time at All." But the show's

virtues are hard pressed to cover its flaws. The book is short on depth or

emotion, and the comedy is mostly in anachronism, or breaking character to

comment on the production. And tho I confess to playing the OCR (produced by

Phil Ramone) for countless hours as a teenager (while I learned to juggle),

it's not a score that ages well like wine. I hadn't seen the show in years,

when I caught an acclaimed Deaf-West production at the Taper in LA. but without

Fosse's gimmicks, the play's bones were so bare I could hardly wait till it was

over. Diane Paulus, Bway's latest "wunderkind" director took on Pippin in 2013, after her previous--and

sometimes controversial--resuscitations of Hair

and Porgy & Bess. Her solution to

the play's hollow center was to drape it in Cirque de Soleiltrappings--hoisting Andrea Martin to aerial gymnastics (and another Tony), and proving once & for all, the show has Magic to Do to disguise its empty air. It would take another Michael Weller rethink (as with Hair) to give Pippin any emotional heft. Without that only a Fosse or another visual fantasist could have brought this to life on screen. But as big a hit as the show was, that passion was never there. Stephen Schwartz was the early '70s Midas of Bway tunesmiths. Pippin was the unlikely smash hit follow up to Godspell, and in '74, a modest framework for magician, Doug Henning, The Magic Show, gave Schwartz a third home run--financially if not artistically. But he stumbled working for David Merrick on The Baker's Wife, and his concept revue, Working never did. He drifted into the Disney stable until his Bway juggernaut, Wicked brought him renewed success. Is there renewed interest in Pippin?

Kander & Ebb started the decade with a near-revue,

featuring a cast of feisty alter-kochers, and ended it with Liza Minelli in a

confessional nightclub act. 70, Girls, 70,

put out a lively album before it quickly expired (it also killed, literally,

longtime Bway musical comedy actor, David Burns--he expired on stage after his

number, out of town); The Act sold well on Liza's name

(and won her a second Tony Award) but wasn't much more than a concert by

one "Michele Craig"--a character, in any case, far less interesting

than Liza herself. The book by George Furth (Company), was apparently intriguing enuf to engage Martin

Scorcese's interest--in tandem with his affair with Minnelli, stemming from

their collaboration on

Kander & Ebb started the decade with a near-revue,

featuring a cast of feisty alter-kochers, and ended it with Liza Minelli in a

confessional nightclub act. 70, Girls, 70,

put out a lively album before it quickly expired (it also killed, literally,

longtime Bway musical comedy actor, David Burns--he expired on stage after his

number, out of town); The Act sold well on Liza's name

(and won her a second Tony Award) but wasn't much more than a concert by

one "Michele Craig"--a character, in any case, far less interesting

than Liza herself. The book by George Furth (Company), was apparently intriguing enuf to engage Martin

Scorcese's interest--in tandem with his affair with Minnelli, stemming from

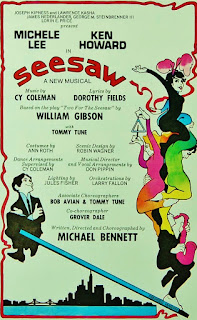

their collaboration on  Cy Coleman struggled for seven years to get another

musical to Bway after Sweet Charity

but Seesaw

was a semi-salvaged flop that suffered as much as it was saved by Michael

Bennett out of town. The source was a two-character play, Two for the Seesaw which was awkwardly expanded to a 50 member ensemble;

essentially a third character: the City of New York--the gritty, bankrupt,

scary NY of the '70s. Anne Bancroft & Shirley MacLaine played the hapless

heroine, Gittel Mosca on stage and on screen. Lainie Kazan took the musical

lead, but Bennett fired her in

Cy Coleman struggled for seven years to get another

musical to Bway after Sweet Charity

but Seesaw

was a semi-salvaged flop that suffered as much as it was saved by Michael

Bennett out of town. The source was a two-character play, Two for the Seesaw which was awkwardly expanded to a 50 member ensemble;

essentially a third character: the City of New York--the gritty, bankrupt,

scary NY of the '70s. Anne Bancroft & Shirley MacLaine played the hapless

heroine, Gittel Mosca on stage and on screen. Lainie Kazan took the musical

lead, but Bennett fired her in  Nor was I Love My Wife, which had just four

characters, plus a four-man band who served onstage as chorus as well--a very

Off-B'way sized musical, which became Coleman's longest running Bway show thus

far. Michael Stewart's book tackled social mores with a pen dipped in Disney.

The sexual revolution suitable for family audiences--a suburban

Nor was I Love My Wife, which had just four

characters, plus a four-man band who served onstage as chorus as well--a very

Off-B'way sized musical, which became Coleman's longest running Bway show thus

far. Michael Stewart's book tackled social mores with a pen dipped in Disney.

The sexual revolution suitable for family audiences--a suburban  Coleman's next show hit Bway barely ten months later, and

was all the more amazing for its musical nuance and complexity. On

the 20th Century took off like a locomotive (figuratively as well

as literally) and blew me away. Cy's Rossini-flavored score is, along with Sweet Charity, his very best--and most

unexpected--work ever; Comden & Green's book & lyrics are a model of

economy and an improvement on the original play and movie; and Harold Prince's

Art Deco production was spic 'n' span in finesse and utility. Likewise the cast

could hardly be better: John Cullum, Imogene Coca, and Kevin Kline--turning a small supporting role into a Star-making part.

Coleman's next show hit Bway barely ten months later, and

was all the more amazing for its musical nuance and complexity. On

the 20th Century took off like a locomotive (figuratively as well

as literally) and blew me away. Cy's Rossini-flavored score is, along with Sweet Charity, his very best--and most

unexpected--work ever; Comden & Green's book & lyrics are a model of

economy and an improvement on the original play and movie; and Harold Prince's

Art Deco production was spic 'n' span in finesse and utility. Likewise the cast

could hardly be better: John Cullum, Imogene Coca, and Kevin Kline--turning a small supporting role into a Star-making part. And then there's Madeline Kahn, who under the strain of her most taxing role, notoriously clashed & burned with the producers and Prince, only to be replaced after two months by Judy Kaye, hailed, almost punitively, as the Big Star Discovery. Kaye, who I later saw (twice) as well, was fine, and continues a long, varied and rich career in a variety of roles, but I didn't see her blazing as brightly as Kahn--at least in the two performances I saw Madeline, when she was fully on--which apparently wasn't with regularity. She was magnificent. With her and Coca on one stage, it was a bounty of female comic talent. Add Cullum, Kline, and the propulsive score; and it's a cornucopia. One of the few musicals I was obsessed with during this period, in case you couldn't tell. In my many focussed listenings of the OCR, I concocted a visual image of the show that had great screen potential. A cross of '30s MGM with German Expressionism, entirely studio set, and with angle-shot close-ups like comic strip panels. It seemed dandy. But then, I had long refused to accept that the score--the show's greatest asset--is to most ears considered operetta--which I think limited its success. I, too, was allergic to what I thought was operetta, and my taste never strayed down that alley. But this, to me, was a true, artfully crafted, musical comedy score. If this was operetta, it was Cy Coleman's take on the genre, hardly reminiscent of Romberg or Friml. But when a show this good barely ekes out a years run on Bway. what chance is there of a Hlwd movie? The musical languished for decades until a revival was mounted in 2015 as a showcase for Kristin Chenoweth--a role eminently suited to her comic and vocal abilities (unlike her miscast stints in The Music Man, or Promises, Promises). But On the 20th Century is as out of time in the 21st--an opera bouffe in a comic book world. I have little doubt had it first unveiled in The Golden Age it would be as much in the canon today as Pajama Game or Hello, Dolly! Like everything, it's all in the timing.

They're Playing Our Song was another two-hander, buttressed with a

couple of backup trios; one male, one female. It was a low cost affair, written

by Neil Simon in his sleep, a show that exemplifies the '70s Bway ethos: scaled

down production, spare plot, tinkly pop score. A hit for the suburban bourgeoisie.

And as such: another natural for the movies. Especially in the Reagan era, when

Simon was recycling nearly all his stage output on screeen, between his slew of

new sceenplays. This one was "When Marvin Met Carole," a

fictionalized romance between a composer & lyricst, much like the authors

of this very show: Marvin Hamlisch & Carole Bayer Sager--he's steady, she's

a lovable nutjob. Their score sounds like a demo to win a track on Barbra

Streisand's "Songbird" album. She and Hamlisch had already struck

gold with "The Way We Were," and she would be prominent among his

praisers upon his death in 2012. On Bway They're

Playing Our Song got away with Lucie Arnaz (and Robert Klein)--neither much

of a singer, tho Arnaz was far superior to her mother, Lucy (admittedly a low

bar.) Stockard Channing, Anita Gillette

and Ellen Greene were replacements, but a film would require a Star. After

Streisand's 1979 Main Event misfire

(which, incidentally, was the point she fell off the cliff of my interest) she

mght well have considered this piece of fluff instead of a trainwreck like All Night Long. Barbra was surely suited

for Simon's heroine, a kooky neurotic, always dressing in cast-off stage

costumes, forever breaking up with her unseen boyfriend. As her exasperated

writing partner, Steve Martin would've been rather nifty. Almost makes you want

to see it. The show wasn't long on music to begin with, full of typical Neil

Simon dialogues and gags. The musical's score (even with Sager's thuddingly

pedestrian lyrics) might have had a hit or two with Streisand, something it

didn't generate otherwise.

No one dominated musical theater more in the '70s than

Sondheim (who needs no first name) beginning with Company, which felt like

the future, but was really just Sondheim, who, tho often-imitated is rarely

equaled. And that's much the problem with musicals in his wake; brilliant as

Sondheim's shows are, they're mistakenly held as the path to Bway's salvation.

Instead they opened a boutique niche; musicals for the connosieur not the

masses. I still remember the feeling of strangeness sitting in the balcony of

the

No one dominated musical theater more in the '70s than

Sondheim (who needs no first name) beginning with Company, which felt like

the future, but was really just Sondheim, who, tho often-imitated is rarely

equaled. And that's much the problem with musicals in his wake; brilliant as

Sondheim's shows are, they're mistakenly held as the path to Bway's salvation.

Instead they opened a boutique niche; musicals for the connosieur not the

masses. I still remember the feeling of strangeness sitting in the balcony of

the

You can see the studios shaking their heads over the

show's screen potential. First off. the score was too sophisticated--thought

too adult for general public ears. Remember, it took decades for Sondheim to

dissolve into the public bloodstream. George Furth's book was less a story than

a string of vignettes--pushing the concept musical into further abstraction;

heightened by the geometric patterns of the staging. I didn't see how a movie

was remotely possible. Then several years ago, it suddenly seemed clear to me

how it should've been done. Where the show was abstract, the film would be

literal; lensed entirely in New York

Another orgy of casting gamesmanship clings to Follies

like the ghosts within the show. Less than a year after Company, Sondheim, Prince & Bennett gave birth to a spectacle

forever eulogized as the Be All & End All. (I consider it the last gasp of The Golden Age --both for its thematic as well as symbolic deconstruction of the

musical.) It had quite a buzz around it when it opened in April '71, but it

never quite reached that SRO hysteria a hit takes on. "Nostalgia" was

trend du jour around Bway that

spring, with mobs clamoring for the old-fashioned comforts of No, No, Nanette; exiting in giddy

satisfaction; a congregation in joy. But Follies

was a touch too bitter; people came out conflicted, unsure, lost in thought.

For those with show-envy I saw that original production at the Winter Garden 3

times. And much as I was mad for it, somehow it hasn't remained among my top

theater memories. (I've only to think of Nanette

and I'm smiling.) Unquestionably, Sondheim's score is breathtaking, and more so

for having so much variety; half pastiche (and flawlessly so) and half

signature. But oh, that book! The crumbling marriages in James Goldman's

libretto are the show's albatross, yet without them it's little more than a

revue.

Another orgy of casting gamesmanship clings to Follies

like the ghosts within the show. Less than a year after Company, Sondheim, Prince & Bennett gave birth to a spectacle

forever eulogized as the Be All & End All. (I consider it the last gasp of The Golden Age --both for its thematic as well as symbolic deconstruction of the

musical.) It had quite a buzz around it when it opened in April '71, but it

never quite reached that SRO hysteria a hit takes on. "Nostalgia" was

trend du jour around Bway that

spring, with mobs clamoring for the old-fashioned comforts of No, No, Nanette; exiting in giddy

satisfaction; a congregation in joy. But Follies

was a touch too bitter; people came out conflicted, unsure, lost in thought.

For those with show-envy I saw that original production at the Winter Garden 3

times. And much as I was mad for it, somehow it hasn't remained among my top

theater memories. (I've only to think of Nanette

and I'm smiling.) Unquestionably, Sondheim's score is breathtaking, and more so

for having so much variety; half pastiche (and flawlessly so) and half

signature. But oh, that book! The crumbling marriages in James Goldman's

libretto are the show's albatross, yet without them it's little more than a

revue. There are legions who find the original cast unbeatable.

I'm not one of them. I often find Hal Prince's casting quirky and

disappointing. I've nothing against Alexis Smith, Dorothy Collins, Gene Nelson

or Yvonne DeCarlo--but how much more resonant the show might have been if its

leads had genuine Bway histories in their bones. Mary McCarty, Ethel Shutta,

Fifi D'Orsay--were they anyone's fond recall? And really, couldn't they do

better than John McMartin? The production was spectacular but its lavishness

has hardly gone extinct. I also saw what was surely the show's first revival,

in 1976--at the postage stamp-sized Equity Library theater in NY, (which

surprisingly worked well) with a decidedly unknown cast. It was the 1985

There are legions who find the original cast unbeatable.

I'm not one of them. I often find Hal Prince's casting quirky and

disappointing. I've nothing against Alexis Smith, Dorothy Collins, Gene Nelson

or Yvonne DeCarlo--but how much more resonant the show might have been if its

leads had genuine Bway histories in their bones. Mary McCarty, Ethel Shutta,

Fifi D'Orsay--were they anyone's fond recall? And really, couldn't they do

better than John McMartin? The production was spectacular but its lavishness

has hardly gone extinct. I also saw what was surely the show's first revival,

in 1976--at the postage stamp-sized Equity Library theater in NY, (which

surprisingly worked well) with a decidedly unknown cast. It was the 1985  The Sondheim/Prince Industiral complex rolled on thru the

'70s. A Little Night Music (as

already discussed) came next, then a resuscitation of Bernstein's great Candide (with Sondheim adding new lyrics)

followed by Pacific Overtures, and

topping the decade off with Sweeney Todd.

But film producers weren't snapping these up for the screen. Night Music was made (poorly) as an

indie production and Sweeney Todd had

to wait over 25 years before it was risked by Hlwd. Pacific Overtures was, if

possible, even more resistant to translation, given its very nature as a Kabuki

pageant. The stage musical was however filmed (for TV broadcast in

The Sondheim/Prince Industiral complex rolled on thru the

'70s. A Little Night Music (as

already discussed) came next, then a resuscitation of Bernstein's great Candide (with Sondheim adding new lyrics)

followed by Pacific Overtures, and

topping the decade off with Sweeney Todd.

But film producers weren't snapping these up for the screen. Night Music was made (poorly) as an

indie production and Sweeney Todd had

to wait over 25 years before it was risked by Hlwd. Pacific Overtures was, if

possible, even more resistant to translation, given its very nature as a Kabuki

pageant. The stage musical was however filmed (for TV broadcast in Next Up: Annie

No comments:

Post a Comment