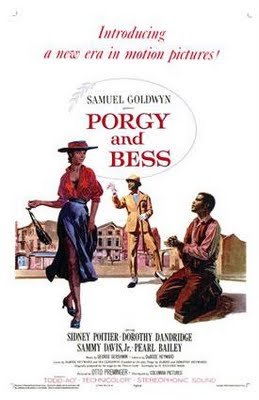

June 24, 1959 Goldwyn 115 minutes

It’s not too surprising I’ve never seen this film before; it was pulled from release in 1974 by the Gershwin estate. It was shown only once on network TV in ‘67, and I wasn’t yet seven during its theatrical release. More surprising is that up to now I’ve never seen any version of Porgy & Bess, nor really bothered to listen to a full recording, unless you count the Ella Fitzgerald/Louis Armstrong album—which really doesn’t count, as any true fan of the Gershwin mastepiece will tell you. So here’s a rare occasion on this journey where I’m a virgin. And like most virgins having their very first time, my feelings are mixed about the film and the work. Of course the true argument is that the work can’t be fairly judged by the film--which is presumably why the Gershwin estate hates it so.

But I’ve done my research and I’m coming up to speed on the opera. For in its purest form it is nothing less than an opera; but one that’s had life as both a musical play and straight drama, and originally a novel. But depictions of African-American ghetto life by an armchair tourist and Southern white gentleman are, by default, subject to controversy. Thus from the start P&B has been vilified as well as lauded. In an odd sort of way, the Negro Objection: to depictions of murder, gambling, drugs, promiscuity, is in part the same reason I’ve shied away from the work for so long. As a child what did I know from black life? I gained consciousness not only in an entirely white world, but a newly built one too. Canoga Park’s most ancient structures were all of 30 years old. In my vicinity there were simply no blacks. They weren’t on TV then, either, aside from the occasional Pearl Bailey or Sammy Davis song & dance segment. Or in news events of civil rights struggles. But certainly not in stories of daily African-American lives and culture. Thus, no matter their folkloric pretensions, stories like Porgy imprint cultural examples that then become points of reference: stereotypes. So while there is nothing inherently—or even factually—wrong with characters or events in an urban slum such as that rendered in P&B, the point is well made that viewing the wretched and unfortunate from across a segregated racial and class divide feels a lot like slumming.

In my peripheral vision, Catfish Row reeked of slums steeped in violence and tragedy. I wasn’t drawn to its Charleston cobblestones. I was an Iowa boy (metaphorically) at heart. The Deep South never held much pull for me; swampy landscapes with turbulent humid weather; uncomfortable racial histories and sweet, heavy food. Serve that up in a big cauldron of ghetto life, but don’t expect me to come running. I can easily see why many African-Americans found offense in such depictions. Even today, in light of the general acceptance of Gangsta Culture, Show Boat and Porgy & Bess can still incite racial objection. Then there’s my Gershwin problem. As part of Bway’s Mt. Rushmore (along with Kern, Berlin, Porter & Rodgers) George has always placed a distant last to me. Granted his symphonic works are glorious, but his songwriting often strikes me as facile and conspicuously overplayed. (He’s the lazy-eared fan’s favorite) There isn’t a song of his that hasn’t a better equivalent from the other big four. That’s not to say that I don’t recognize the achievement of Porgy & Bess—his final masterwork—and ponder just what else he might have written had he lived into the Golden Age—of which he was already at the forefront. But great as the P&B score is (and how could I escape it, with so many covers of “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’,” “It Ain’t Necessarily So,” “Bess You Is My Woman Now,” not to mention a hundred versions of “Summertime”?) I was never drawn to it like a moth to a flame as I have been with even the most egregious of Bway flops such as Whoop Up and How Now Dow Jones. We all have our lapses, I suppose.

In my peripheral vision, Catfish Row reeked of slums steeped in violence and tragedy. I wasn’t drawn to its Charleston cobblestones. I was an Iowa boy (metaphorically) at heart. The Deep South never held much pull for me; swampy landscapes with turbulent humid weather; uncomfortable racial histories and sweet, heavy food. Serve that up in a big cauldron of ghetto life, but don’t expect me to come running. I can easily see why many African-Americans found offense in such depictions. Even today, in light of the general acceptance of Gangsta Culture, Show Boat and Porgy & Bess can still incite racial objection. Then there’s my Gershwin problem. As part of Bway’s Mt. Rushmore (along with Kern, Berlin, Porter & Rodgers) George has always placed a distant last to me. Granted his symphonic works are glorious, but his songwriting often strikes me as facile and conspicuously overplayed. (He’s the lazy-eared fan’s favorite) There isn’t a song of his that hasn’t a better equivalent from the other big four. That’s not to say that I don’t recognize the achievement of Porgy & Bess—his final masterwork—and ponder just what else he might have written had he lived into the Golden Age—of which he was already at the forefront. But great as the P&B score is (and how could I escape it, with so many covers of “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’,” “It Ain’t Necessarily So,” “Bess You Is My Woman Now,” not to mention a hundred versions of “Summertime”?) I was never drawn to it like a moth to a flame as I have been with even the most egregious of Bway flops such as Whoop Up and How Now Dow Jones. We all have our lapses, I suppose.

Hlwd’s Porgy & Bess then is—if you should pardon the expression—a horse of a different color. Originally produced on Bway only because no Opera company had the voices or resources in 1935, it could barely be called a succes d’estime. A revival in ‘42 that stripped the score of recitative brought more attention but a lavish ’53 production brought respect and International acclaim from a world tour that lasted five years, with a particularly rapturous reception in the Soviet Union on a cultural exchange program. (Catfish Row must have been as unknowable and exotic to the Ruskies as it was to me in my Russian/American bubble—except that the Soviets enjoy wallowing in deprivation and misery in a way I never could.) It was this production that forever canonized the show (as opposed to the opera) and started the avalanche of offers from Hlwd: Louis B. Mayer, Hal Wallis, Joseph Mankiewicz, Dore Schary, etc.—which Ira Gershwin declined, including an especially offensive (but longtime rumored) plan of Harry Cohn’s to cast Al Jolson, in an all blackface version, with Rita Hayworth as Bess and Fred Astaire as Sportin’ Life—The Last Minstrel Show. Finally in May ’57, Ira sold the rights for $650,000 to Samuel Goldwyn who was looking for one last prestige offering. Various authors and directors were sought, including Langston Hughes, Clifford Odets, Frank Capra and Elia Kazan. Goldwyn eventually settled on Rouben Mamoulian—not a bad choice considering he’d directed the first Bway production, but also had a fine cinematic eye, and proved just a year earlier he was still in good form with Silk Stockings, and on budget as well. It should have worked out well. But on the verge of filming, virtually the entire set (and costumes) burned down, and the sked was set back six weeks—during which time Goldwyn quarreled with and subsequently fired Mamoulian before a frame had been photographed. The position was quickly filled by Otto Preminger.

Given the cast, it would seem like Otto had been on board from the start. Pearl Bailey, Brock Peters, and Diahann Carroll had all been in Preminger’s Carmen Jones, which had starred Dorothy Dandridge as well (pretty much Hlwd’s entire black rolodex.) The Star and Director had been thru an affair lasting several years, but was now in the past. Still, Dandridge didn’t sign on expecting to face her ex behind the camera, and the shoot was a trial for her. Her Carmen co-star, Harry Belafonte, had first been approached to play Porgy; which he rejected with disgust. Sidney Poitier had reservations as well, but felt pressured (threatened?) by his agent, and took it on as a challenge—on conditions that allowed him to make the film he really wanted to: The Defiant Ones. Poitier aimed to humanize Porgy, using natural speech not the exaggerated dialect of the libretto. He gives a performance very true to Poitier—but is that Porgy? Brock Peters is the towering brute, Crown—and he could scarcely be more towering or brutish; he’s magnificent. Maria isn’t much of a part, and Pearl gets only a verse of one song to herself (“Oh, I Can’t Sit Down”). Like Poitier, she came aboard with demands: no Aunt Jemima bandannas, or bare feet. It seems Sammy Davis Jr. was the only black actor campaigning to be in the film. You can see why; Sportin’ Life is in his DNA. Frankly the character puzzles me the way he so casually and openly dispenses his services around those who revile him; he’s like a gnat forever buzzing around—or a spider, waiting for Bess to fall into his web. Arguably his two numbers are among the most successful; tho “It Ain’t Necessarily So” (an amazing rebuttal to Biblical teaching) is filmed on one of the shabbiest pieces of swampland ever used for a musical number. Still, the cast is pretty stellar, and from an acting standpoint, beyond reproach. Poitier brings his trademark dignity as well as the ferocity of his strength (after all, he overpowers Crown), but when he opens his mouth to sing, Robert McFerrin’s voice comes out, and the aural schism is jarring. Adele Addison dubs Bess, but the match is closer to Dandridge; who does quite right by the role, and at times looks even more ravishing than she did as Carmen Jones. More so than even Lena Horne, Dandridge was a very sexual black woman—and Hlwd was still very timid in allowing or exploiting that. Bess was to be her last major film role. She made only one more movie and one appearance on a TV drama, and in six years she was dead at the age of 42. Tho P&B didn’t quite resurrect her career it remains, along with Carmen Jones, Dandridge’s most iconic role. For all others, the film would never be considered a career highlight. Even Sammy had bigger fish to fry.

With so little time for prep, and so much of the same personnel around, it’s not surprising that Preminger essentially remade Carmen Jones. Both unfortunately steeped in the drabbest of settings—two of the ugliest musicals ever made. Despite a lavish overly-stylized set by the estimable Bway designer Oliver Smith, the film is awash in palettes of rust and ash. The walls scream Disney, but the lights and colors drown everything in shades of dirt and smoke. The film is notoriously remembered for its static camera, but that’s not exactly true. Goldwyn brought on Leon Shamroy, who following the chorus of disapproval from his “technique” on South Pacific, steered clear of any technique whatsoever, filming everything in straight-forward fashion. The camera moves—it just doesn’t move very masterfully, or too often. (To be fair, we are not privy to seeing the original Todd A-O print; bootlegs seem to be all pan & scan.) In what can only be construed as an act of blind Hlwd loyalty, Shamroy won his 15th Oscar nomination for this. The film’s sole Oscar win was to Andre Previn & Ken Darby for their scoring—which dared to veer from Gershwin’s own original orchestrations. Preminger wanted to steer the film in a jazzier direction, but Goldwyn held to his affection for a more symphonic sound; beginning with a lush new overture arranged by Previn—the tail end of which continues as the movie begins: a celluloid curtain parting for the roll of credits, almost pompously unadorned.

The film opens on a washed-out dock with a dubbed Diahann Carroll serenading her baby with “Summertime.” It’s a slice of life moment meant to be transfixing; but the scene is too perfunctory, the setting too drab; it feels clunky instead of hypnotic; not a graceful slide into the milieu—or a curtain rising on stage. Apparently the bootleg copies floating about are 23 minutes short of the original 138 minute release. Perhaps the film was later trimmed for the local bijous, much like South Pacific. And as the film’s intermission point now clocks in at 52 minutes, it’s fair to say that most, if not all, of the cuts seem to be from the early scenes—which may explain why they feel somewhat graceless. There’s an especially blunt cut from the first scene on the docks to the soundstage rooftops of Catfish Row, as Sportin’ Life prances across the parapet and slithers down a drainpipe to join the gathering crap game in the courtyard below. And soon another bad cut to Porgy’s arrival—it feels unnecessarily choppy. The set of this faded Charleston apartment house is too stylized for film. Musicals & naturalism are not an easy fit (which explains why so many musicals are about show business), and while the stage is by nature dependent on representation, cinematography begs for a visual reality that isn’t quite achieved here.

Goldwyn’s choice of screenwriter was an odd one: N. Richard Nash, known primarily for his prairie romance, The Rainmaker (then recently filmed with Katharine Hepburn & Burt Lancaster). Nash stripped away every bit of recitative, wrote whole scenes of dialogue but cut to the bone. Just about the entire score of the opera is heard, tho many numbers are abridged, and other, mostly choral sections are used as scene bridges or background. The story moves along at a clip; after the opening introductions we’re on to a dice game, a drunken dispute, a murder, and a junkie forced to take shelter with a cripple. (Bess seems to quit her habit quite easily) In short order Porgy is bragging “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’” but “Bess, You is My Woman Now.” This bliss is soon ruptured after a community picnic on an island (which treads on awfully familiar territory from Carousel—tho of course, P&B came first) where events eventually lead to another death. Bess is raped by her ex, Crown—and takes ill for a week. Nursed back to life by Porgy, their bond is strengthened as she confesses, “I Loves You, Porgy.” All this drama stirs up a hurricane, which draws the cast together in a church house, with Crown returning to reassert his menace. He leaves to play hero (tho he fails), and upon his return is killed by Porgy in self-defense. Porgy is taken away by the police—not as a suspect, but to identify Crown’s body. But Sportin’ Life spooks him into believing a voodoo tale that looking into Crown’s face will make the wounds bleed, thus revealing Porgy’s guilt. (Was there really such a superstition or was it made up for this story? If so, it feels silly and patronizing—especially for someone so grounded, so to speak, and level-headed as Porgy to believe it.) Incidentally, we never know anything about him; the cause of his affliction, his family or past—it’s all irrelevant in the script, tho I can’t speak for the novel. Of course the same goes for all the characters, including Bess. But how an impoverished black woman becomes a thug’s moll and junkie doesn’t take much imagination. Porgy’s affliction requires an entire performance on knees—it can’t be easy on any actor, but isn’t it also a strain for the audience? Each time we watch Poitier drag his calf-length slats across the cobble-stones, or painstakingly climb the stairs to the church house we’re milked for sympathy. He’s such the Noble Negro that his disability gifts him spiritual powers; he explains: “God give cripple to understand lots of things he didn’t give strong men.” Yet Bess’s love and devotion is built of straw, for when Porgy is carted off in the Black Mariah, she takes all of 30 seconds to move from vehement refusal, to snorting “happy dust” (notice how they always turn away so as not to show us how it’s done.) When Porgy returns but a week later, she’s gone with Sportin’ Life to New York; not even the infant, fated to her care after the deadly hurricane, is enuf to anchor her. Talk about skanky! Bess is the antithesis of Julie Jordan—who goes thru life devoted to a brute she knew for mere days; Bess doesn’t even wait a fortnight for her beloved and honorable man. When stories of African-American culture are so few and far between, you can see why the show—no matter its classic score—can feel unsavory and condescending. Take the song, “I Ain’t Got No Shame (Doin’ What I Likes to Do)” heard as background only here—but what a sentiment! Would they dare to depict any other minority in need of decrying their own self-shame? It feels insulting in its patronization—oh, those carefree colored folk! They even dance like wild jungle monkeys at the end of “It Ain’t Necessarily So,” in the voodoo grip of Sportin’ Life’s counter-sermon. I found the ending even more insulting: Porgy riding off on his goat wagon—as impulsively as Hans Christian Andersen setting off for Wonderful Copenhagen—to chase Bess to New York (and would he really not have ever heard of the place?) The great uplifting chorus helping him along with “Oh, Lawd, I’m On My Way,” which under the circumstances sounds like a death march. He doesn’t even grab so much as a sweater—the neighbors cheering him on: Good luck, Porgy! It’d be a miracle if he got as far as North Carolina. For a story steeped in melodramatic realism, this fairy tale ending reaches for unearned optimism. (In the novel Porgy resumes his lowly existence in Catfish Row.) But these cavils are generally swept under the rug of artistic appreciation. Like it or not, this is a major American opera—and a popular one at that—whose fame and quality cannot be denied.

Many Musical lovers venture into Opera and Operetta with equal enthusiasm. I am not one of them. My problem with opera is that I like a balance between song and scene—continuous music is a strain on my ear, recitative washes out the impact when my ears are supposed to perk up. (Sung-thru musicals can be just as exhausting and frankly, as in the case of Andrew Lloyd Webber, purely a narcissistic indulgence—and no favor to any audience.) Watching a full opera staging of Porgy & Bess (Trevor Nunn’s Glyndebourne Festival production, if you must know), which came highly recommended, put me in the camp of those who prefer their P&B cut to the Bway cloth. The opera feels like, well…an opera—and much of the dramatic action has less impact; more artificiality. In a funny way it gave me new respect for the movie—or at least Goldwyn’s attempt to make a P&B for the general public. Watching the movie again after viewing an opera staging, I found it strangely more gripping. But then the many volumes of scholarship on Gershwin attest to a constant shifting of opinion concerning the score in its most effective presentation. The ’53 revival, which stripped the recitative out almost entirely to create the purest “Musical” version, heralded the start of an avalanche of recordings, a good majority of them in jazz or pop vocal mode, including a landmark Miles Davis album with Gil Evans’ orchestra, and the 2-disc Verve set featuring Louis & Ella. (There were other pairings forthcoming, many of them in the wake of Goldwyn’s movie: Harry Belafonte & Lena Horne; Sammy Davis & Carmen MacRae; and a real headscratcher, but nonetheless rather highly regarded: Mel Torme & Francis Faye—a bulldyke Bess!) The film’s soundtrack was no slouch either, charting on Billboard’s Top 100 for 96 weeks, climbing to the #8 position. The show’s popularity peaked around Goldwyn’s movie but with the rise of civil unrest, and the great societal changes over the next two decades it abated. The show’s relevance was at distinct odds with the zeitgeist, yet a bicentennial production from the Houston Opera began a new renaissance for the opera. Time only renders the cultural objections more irrelevant. As with Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the work requires a contemporary blind eye to racial insensitivities to be accepted as the product of another era; folklore that allows us the view of simultaneously appreciating the piece and seeing how far we’ve grown in our changing racial landscape. However one feels about it, Porgy & Bess has attained the status of a Classic—a landmark that Stephen Sondheim extols: “There’s P&B, and there’s everything else.” (To which I say, thank God for Everything Else.) And so it goes… Now a newly reconceived production to star Audra MacDonald & Norm Lewis is on its way.

Many Musical lovers venture into Opera and Operetta with equal enthusiasm. I am not one of them. My problem with opera is that I like a balance between song and scene—continuous music is a strain on my ear, recitative washes out the impact when my ears are supposed to perk up. (Sung-thru musicals can be just as exhausting and frankly, as in the case of Andrew Lloyd Webber, purely a narcissistic indulgence—and no favor to any audience.) Watching a full opera staging of Porgy & Bess (Trevor Nunn’s Glyndebourne Festival production, if you must know), which came highly recommended, put me in the camp of those who prefer their P&B cut to the Bway cloth. The opera feels like, well…an opera—and much of the dramatic action has less impact; more artificiality. In a funny way it gave me new respect for the movie—or at least Goldwyn’s attempt to make a P&B for the general public. Watching the movie again after viewing an opera staging, I found it strangely more gripping. But then the many volumes of scholarship on Gershwin attest to a constant shifting of opinion concerning the score in its most effective presentation. The ’53 revival, which stripped the recitative out almost entirely to create the purest “Musical” version, heralded the start of an avalanche of recordings, a good majority of them in jazz or pop vocal mode, including a landmark Miles Davis album with Gil Evans’ orchestra, and the 2-disc Verve set featuring Louis & Ella. (There were other pairings forthcoming, many of them in the wake of Goldwyn’s movie: Harry Belafonte & Lena Horne; Sammy Davis & Carmen MacRae; and a real headscratcher, but nonetheless rather highly regarded: Mel Torme & Francis Faye—a bulldyke Bess!) The film’s soundtrack was no slouch either, charting on Billboard’s Top 100 for 96 weeks, climbing to the #8 position. The show’s popularity peaked around Goldwyn’s movie but with the rise of civil unrest, and the great societal changes over the next two decades it abated. The show’s relevance was at distinct odds with the zeitgeist, yet a bicentennial production from the Houston Opera began a new renaissance for the opera. Time only renders the cultural objections more irrelevant. As with Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the work requires a contemporary blind eye to racial insensitivities to be accepted as the product of another era; folklore that allows us the view of simultaneously appreciating the piece and seeing how far we’ve grown in our changing racial landscape. However one feels about it, Porgy & Bess has attained the status of a Classic—a landmark that Stephen Sondheim extols: “There’s P&B, and there’s everything else.” (To which I say, thank God for Everything Else.) And so it goes… Now a newly reconceived production to star Audra MacDonald & Norm Lewis is on its way.

For Sam Goldwyn, Porgy & Bess was his 80th and final film. He had really wanted to get his hands on The Diary of Anne Frank, but when that fell thru he grabbed for another highly coveted prize—one he had loved and admired since the ‘30s. His swan song required Prestige with a capital P. And in 1959 that demanded a Roadshow release. The movie opened June 24, 1959 at the Warner Theater in Times Square. It was a banner month on Bway: the season’s new musicals were all SRO: R&H’s Flower Drum Song, Redhead with Gwen Verdon; Dolores Gray in Destry Rides Again; the French revue La Plume de ma Tante; and the just opened, record-grossing smash, Gypsy. My Fair Lady and The Music Man gave no hint of slowing down. West Side Story closed that weekend, but it would be back and bigger than ever, soon enuf. New plays destined for Hlwd were also on the boards: The World of Suzie Wong, A Majority of One, The Pleasure of His Company and Tennessee Williams’ Sweet Bird of Youth. One other hit, Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun was another landmark Negro drama; one whose honesty and realism seemed to throw some shade on the quaint folklore of Porgy & Bess. (Hansberry debated Goldwyn on television [without having seen the film no less], railing at the depiction of blacks as “exotics”—a fact Goldwyn did not dispute, as he felt the same, but thought that a positive thing.) It must have galled her to see Raisin (also with Sidney Poitier) playing virtually side by side with P&B on West 47th St. The film’s reserved seat engagement held on for a solid 31 weeks; not bad. But this was New York, and aside from a few other major cities, the movie wasn’t selling popcorn across America; certainly not in the South, where it was equally unpopular with both blacks & whites. The movie performed nothing like Goldwyn’s penultimate smash, Guys & Dolls; barely making back half its $6 million budget. Not only a commercial disappointment, the film was somehow responsible in tarnishing the show’s cachet. Whereas many of Bway’s golden treasures are eventually best known and remembered by their movies—whether good or bad—P&B has transcended its celluloid preservation (in part thanks to the Gershwin lock on it, for sure) by the sheer force of its insistence on being the most famous American opera of the 20th century. And no Otto Preminger opus is going to be the defining word on that subject.

Next Up: Li'l Abner

Next Up: Li'l Abner

Report Card: Porgy & Bess

Overall Film: C

Bway Fidelity: B- shifting scenes, no cutting

Songs from Bway: 21 many adbridged

Songs Cut from Bway: 3 “The Buzzard Song”

“Woman to Lady” (Divorce Scene)

“Time & Time Again”

New Songs: None

Standout Numbers: “I Got Plenty of Nuttin’ ”

“Oh, I Can’t Sit Down”

Casting: The cream of Afro-Hlwd

Standout Cast: Dandridge, Brock Peters

Cast from Bway: Moses LarMarr (Nelson)

Helen Thigpen (Strawberry Woman)

Direction: Plodding, unimaginative

Choreography: atypical Hermes Pan

Ballet: None

Scenic Design: Clapboard, brick & soot

Costumes: Rags by Irene Sharaff

Standout Set: Catfish Row

Titles: Amishly plain

Oscar Noms: 4; one win: scoring

(costumes, cinematography, sound)

Weird Hall of Fame: “It Ain’t Necessarily So”

(swampland dance)

1 comment:

We all have our favourite film or television series that we never get tired of watching. There is something special about films made in Hollywood that fascinates and intrigues us as viewers.Movies are also a source of inspiration to many. There are many people in this world who have been inspired by movies to do something big in their lives. For example, movie based on biographies of great people have influenced people to attain the same pinnacle in their lives.

Clapboard

Post a Comment